In spite of great productivity in particulars, dogmatic rigidity prevailed in matters of principle: In the beginning (if there was such a thing), God created Newton’s laws of motion together with the necessary masses and forces. This is all; everything beyond this follows from the development of appropriate mathematical methods by means of deduction.

– Albert Einstein

I cannot think of more important news I could possibly give you—than that the way we think has been proven wrong.

Because when that happens—the unthinkable becomes possible!

And I don’t only mean the unthinkable tragedy—which Russell and Einstein warned us about (as I reminded you in the About article); when they told us that we have to to learn to think in a new way.

But also an unthinkable blossoming—which we’ll be able to foster when we do learn to think in a new way; which is what the holotopia vision points to.

What is not possible is that the world will remain as it is.

What is that way of thinking that has been “proven wrong”?

I’ll delineate it by using narrow frame as keyword.

And by qualifying the word “wrong”—by turning also the word truth into a keyword; which I’ll use (no longer to say that something “really is” as claimed, but) to delineate that something is both reliable and relied on.

Truth is society-and-culture’s most basic need.

Because it organizes us and empowers us to do what we have to do; because it turns us into a society-and-culture.

Notice that truth has not always been as it is.

Traditional people believed that truth had been revealed to their holy ancestors; and recorded in their holy books.

We believe that truth is revealed to the human mind.

And it is in that transition—from tradition (where people lived as prescribed) and modernity (when we rely on reasoning and comprehension) that things went awfully awry; which is why we now have to undo certain parts of what’s been done, and redo some other parts all over again.

I tried to make this clear in the About article: I am not here to philosophize about the world.

My aim—my only aim—is to prototype and set in motion a process.

And that process is, in my view, just as much your “interest” or “job” as it is mine. So let me now, to that end, tell you how I see what went wrong.

In Knowledge Federation as Ecosophy I’ll offer you a concrete proposal how to correct it (by developing transdisciplinary science; as modernity‘s due way to truth); and in Transdisciplinarity Is a Way to Change Course I’ll demonstrate that the proposed way to truth can guide us to the changes we have to make (that it can turn the present downward spiral into an upward one).

We—and others—can then have a dialog; and concretize and streamline the process of change.

The Narrow Frame Way to Truth

Is one plus one three? Is two plus two four?

I can ask you infinitely many questions of this kind.

And every time you’ll be able to give me a correct answer; and every educated person will be able to verify your answer. And if you may still be in doubt—you can put two pairs of matches together and count the result.

Arithmetic is an example of a formal system; where a certain (necessarily finite, so that it may be written up in books and taught) set of concepts and rules enables us to determine—for all pertinent claims—whether they are true or not.

The narrow frame way to truth, as I’ll be using these words, is an attempt to apply something like the formal system approach in all walks of life; based on the assumption—which is ordinarily taken for granted without being stated—that it simply is the way to truth. In the sciences, this may be reflected as the quest for a theory (for a finite set of concepts and rules) which can be used to explain (make comprehensible to the mind, through “logical” or causal reasoning) what is or is not the case. In public informing this may be reflected as telling people what goes on in the world; and assuming (without giving it much thought) that (based on this as “reality picture” or those “facts”) a “normal” human mind can delineate whether something is true or not by just thinking “logically”.

The Aha! experience that results when the mind has comprehended an argument leading to a conclusion is then used as the litmus test for asserting that this conclusion is indeed true.

Instead of theorizing further, I’ll illustrate the narrow frame way to truth by an example.

By giving us certain “scientific” concepts (“mass”, “momentum”, “force”…) and certain mathematical concepts and procedures to operate on them (“vector”, “derivative”, “integral”…) —Newton in effect turned (our comprehension of) the physical world into a formal system!

The human mind was enormously empowered: On the one side, we became able to fly to the Moon and back (and create innumerable wonders of technology); and on the other, we understood that women can’t fly on brooms (and dispelled countless prejudices and superstitions). The lightning was no longer seen as punishment from beyond—but as electrical discharge.

We could put a lightning rod on the roof!

By explaining also life and its origins in this “scientific” way—Darwin delivered a fatal blow to the traditional way to truth; and if the clarity and empowerment that science brought along were not enough—the necessity to keep up with the advances in technology and weaponry, and the new mores spread by movies and TV, made “the scientific worldview” compelling.

And so science became modernity‘s way to truth; and it ended up spreading globally.

But science—conceived as a collection of traditional disciplines, each minding its own business—never really adapted to this much larger role.

While we are told to think in a “scientific” way—we are not told what this is supposed to mean when applied to life’s core themes! And so in practice—we ended up parroting the narrow frame way to truth:

We believe what makes sense (by reasoning based on what we “know”); and we disbelieve all the rest.

And so, for instance, that we humans should compete to survive, and that the stronger should prevail, made sense; and ended up not only believing in it—but also using it, with clear consistency, to organize our society-and-culture.

Even the academy has “publish or perish” as its rule of thumb!

That we humans should work without regard for the fruits of our work (as Krishna taught Arjuna in the Bhagavad Gita), or that we should be unconcerned about food and clothing (as Christ taught his disciples in the Sermon on the Mount) didn’t make sense.

And so the rules of this kind didn’t influence our society-and-culture.

Fundamental Anomalies

I use anomaly as keyword to demonstrate that we are in a similar situation in our pursuit of truth in general as the scientific disciplines are when (as Thomas Kuhn demonstrated) “new paradigms” are sought and developed.

An anomaly is what drives a paradigm shift (a broadening or replacement of a “scientific theory”—or any other narrow frame).

Experimental evidence of something that is not as the theory predicts constitutes an anomaly; and so does the evidence that something is the case—but we have no theory to explain it. I will now show you four fundamental anomalies (and leave pragmatic anomalies for a later blog post).

And use them to make a case for discrediting and abolishing the narrow frame way to truth; and for developing and instituting transdisciplinary science in its stead.

What if there is no finite set of concepts and rules that delineate all truth in a domain of interest?

Here’s what Google’s AI just told me:

Gödel’s theorem, specifically his first incompleteness theorem, states that in any consistent formal system capable of expressing arithmetic, there will always be true statements that cannot be proved within that system. This theorem has profound implications for mathematics and logic, demonstrating inherent limitations in the capacity of formal systems to capture all mathematical truths.

See what this means:

The narrow frame way to truth doesn’t work even in mathematics!

This second anomaly will show that the narrow frame way to truth doesn’t work even in physics.

I represent it here by the so-called “double-slit experiment”; a description of which you’ll easily find online. So let me here only highlight this key point:

The human mind cannot comprehend the behavior of quanta of energy-matter; we cannot even describe that behavior in conventional language.

The paradigm shift in physics that resulted (which led Kuhn—who was originally a physicist—to formulate his theory of scientific revolutions) was more than just an update of concepts and theories; it was an update of the conception of truth itself.

The physicists understood that the world—the physical world—cannot be comprehended!

Our common sense—Robert Oppenheimer explained in Uncommon Sense—evolved as a way to make sense of things in common experience; there is no reason to expect that it will work when applied to the things we don’t have in experience—such as the quanta of energy-matter. And in The Character of Physical Law, Richard Feynman explained how the character of the way to truth changed in physics.

What resulted is precisely what I’ll propose (in Knowledge Federation as Ecosophy) to use as venture point for developing transdisciplinary science.

What made me change the focus of my research to the issues at hand (or metaphorically, to seek and find a way through the mirror) was Werner Heisenberg’s book Physics and Philosophy; and that’s also where the narrow frame as keyword came from.

Heisenberg wrote this book to bring to our attention the issue we now have to focus on.

Which is that a certain “narrow and rigid” way to truth—which had been immensely successful in physics—ended up being destructive of culture; and that the fundamental findings reached in his field (Heisenberg got his Nobel Prize “for the creation of quantum mechanics”, which he achieved while in his twenties) constituted a rigorous disproof of that approach to truth.

Here is how I attempted to explain Heisenberg’s insight—and how it gives us the mandate to work toward cultural revival—in the Holotopia book manuscript.

Did you get Heisenberg’s point?

We’ve thrown out the baby with the bathwater!

While it helped us dispel countless prejudices and illusions—the narrow frame way to truth destroyed the very foundation on which culture had been evolving.

The third anomaly will explain how the narrow frame way to truth made “democracy” dysfunctional; and why the humanities and social sciences cannot be “scientific” by emulating it as a template.

Here too the anomaly will be a most basic insight reached in an academic field (the systems sciences; or the system complexity theory). This is how I explained in the Holotopia manuscript (I used materialism as keyword instead of narrow frame).

That modernity‘s governance or “democracy” cannot function as it’s been conceived was Forrester’s main point!

And it’s easy to see how his insight leads to a similar conclusion about the humanities and social sciences too:

Both the human being and the society-and-culture are complex systems.

Which cannot be comprehended by the narrow frame approach!

This fourth and last fundamental anomaly is the most spectacular among them.

I invite you to see this jungle that constitutes our information, and our frantic hyperactivity in producing documents (which, as Neil Postman pointed out, not only fail to make the world comprehensible—but also directly damages our ability to comprehend) as consequences of the deep-seated belief that the production of “reality descriptions” is our job.

And that we can leave it to the mind to figure out the truth.

Reification as Root Anomaly

“There are a thousand hacking at the branches of evil to one who is striking at the root”, Henry David Thoreau famously wrote.

In what follows I’ll demonstrate that the mentioned fundamental anomalies have a shared deeper or root anomaly; which (I will demonstrate in a later blog post) is also the root cause of our “problems”.

I’ll call it reification.

And outline how I ended up explaining to myself (and leave the final verdict to our dialog) where reification came from; and how the scientists ended up debunking it and disowning it.

Reification is the act of attributing the “reality” status to the products of human mind.

Including that so comforting Aha! experience that our minds tend to produce.

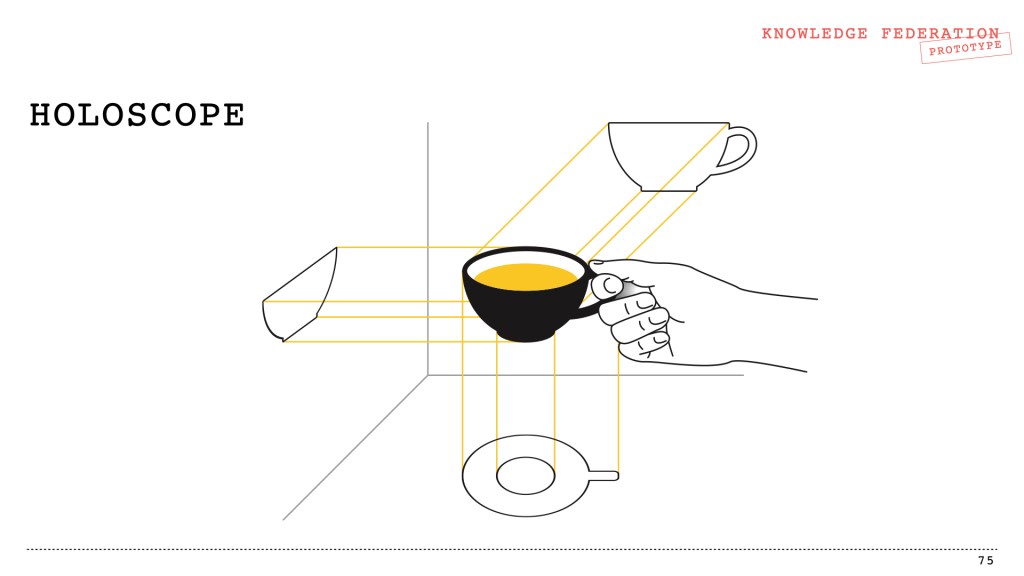

This could be a good place to tell you what the word holoscope here means—and at the same time use that word to clarity reification.

The metaphor suggested by the name is intended to make this point obvious: The microscope and the telescope enabled us to see the things that were too small or too distant to be seen by the naked eye.

The holoscope enables us to see things whole.

To see what this practically means, consider the projection planes in the holoscope ideogram as distinct ways of looking at a theme (which may be given to us by academic disciplines, or by world traditions).

Then (the ideogram makes this obvious) we can see things whole only by deliberately avoiding the mind’s natural urge to hold onto and reify a single way of looking.

I talked with Noah about reification the other day, in one of our epistemology dialogs. To begin it, I reminded him of the iconic image of Galilei in house arrest, whispering “And yet it moves!”

Galilei was in house arrest a century after Copernicus!

So we are inclined to ask: What took those people so long to see the obvious?

But imagine, I told Noah, the people four centuries from now looking back at our time and asking What took them so long…?

What is the “obvious” thing that we don’t see?

I know—that’s not an easy question; it’s a tall order for a fifteen-year-old. So I gave Noah this clue: The answer is in Galilei’s iconic image itself (“And yet it moves!” is not historical; it reflects how we see what was going on back then). Do you see now what I’m pointing at?

Whether the Earth is moving or not is entirely a matter of convention!

It’s an artifact of the way we look at the world.

And that’s a mathematical fact!

Aren’t we free to put the origin of a coordinate system anywhere we please? So why not place it right into the center of our home planet!? And see the cosmos as it appears to us! You already know the answer:

Sscience could not be developed by looking in that way.

Mathematical principles of natural philosophy could not have be formulated; the human mind would not have comprehended the physical world with mathematical precision; technology could not have been developed.

But can you and I—can we as academy, in a grand leap of insight, abolish the habit of reifying the “scientific” way to see the world? And any other way to see the world?

Notice that this is precisely what the mirror metaphor invites us to do.

Descartes too committed a reification; and this is well known.

He wrote in Meditations on First Philosophy:

Some years ago I was struck by the large number of falsehoods that I had accepted as true in my childhood, and by the highly doubtful nature of the whole edifice that I had subsequently based on them. I realized that it was necessary, once in the course of my life, to demolish everything completely and start again right from the foundations if I wanted to establish anything at all in the sciences that was stable and likely to last.

And conducted his quest (for a solid new “foundation”) by doubting whatever he was able to doubt; and concluded it, famously, by finding something he was unable to doubt; and then used that as the foundation on which “the whole edifice” was to be reconstructed.

Descartes—a mathematician at heart—was gratified by the logical clarity and certainty that the narrow frame way to truth provided. But he was alarmed (and this is not commonly known) by its practical consequences! So he wrote—in his unfinished work Règles pour la direction de l’esprit (Rules for the Direction of the Mind), as Rule One:

The objective of studies needs to be to direct the mind so that it bears solid and true judgments about everything that presents itself to it.

In the explanation of Rule One Descartes pointed to academic specialization as the impediment to practicing Rule One:

In truth, it surprises me that almost everyone studies with greatest care the customs of men, the properties of the plants, the movements of the planets, the transformations of metals and other similar objects of study, while almost nobody reflects about sound judgment or about this universal wisdom, while all the other things need to be appreciated less for themselves than because they have a certain relationship to it. It is then not without reason that we pose this rule as the first among all, because nothing removes us further from the seeking of truth, than to orient our studies not towards this general goal, but towards the particular ones.

So yes, we definitely do not want to believe in any sort of nonsense; truth is what we want, and what we necessitate.

But not at the cost of directing the mind to bear solid and true judgments about only some very narrow choice of themes—and ignoring all others!

Can we have both? Can science be updated—so that it enables the mind to bear solid and true judgments about everything that presents itself to it?

Einstein wrote in “Remarks on Bertrand Russell’s Theory of Knowledge”:

During philosophy’s childhood it was rather generally believed that it is possible to find everything which can be known by means of mere reflection. It was an illusion which anyone can easily understand if, for a moment, he dismisses what he has learned from later philosophy and from natural science….Someone, indeed, might even raise the question whether, without something of this illusion, anything really great can be achieved in the realm of philosophic thought—but we do not wish to ask this question.

Notice Einstein’s understatement: The question he’s asking (and then choosing not to ask) is whether philosophy as we’ve known it (which tends to—and arguably has to—rely on “mere reflection”) would even be possible “without something of this illusion”.

Einstein then turned to science; and to our everyday life and culture:

This more aristocratic illusion concerning the unlimited penetrative power of thought has as its counterpart the more plebeian illusion of naive realism, according to which things “are” as they are perceived by us through our senses. This illusion dominates the daily life of men and of animals; it is also the point of departure in all of the sciences, especially of the natural sciences.

In Autobiographical Notes and elsewhere, Einstein clearly expressed his conviction or “credo” that we construct “reality” (and do not discover it as something objectively pre-existing); and so did other thought leaders of 20th century science and philosophy.

In this way, reification (or “reality construction”) was seen as something that we (or more precisely our minds, and our society-and-culture) do.

And so reification itself became a subject of study—in the humanities and social sciences.

The outcome that should interest us is that the scientists found out (not only that “reality construction” is a cognitive and social phenomenon, but also) that reification has been used throughout history as an instrument of power.

Here is how I attempted to point this out in the Holotopia book manuscript.

You may now easily comprehend the strategy or course of action that the cover page of the Holotopia manuscript is pointing at.

We can—and we have to—liberate our students and our children from the “reality” that we ourselves are still confined to.

We have to empower our next generation to create a different and better “reality”.

When I began to study reification in earnest, I read that (verbal communication and comprehension being relatively recent developments in evolution) older parts of the brain, which had served for vision, were adapted for that function. So I amused myself by coining “believing is seeing” as a slogan: We all know that “seeing is believing”; now it has turned out that also the reverse is true—in a physiological and anatomical sense.

Is this the reason why mental comprehension gives us similar physiological rewards as vision does?

We even say, when we’ve comprehended something, “I see”!

When it comes to “mind’s place in nature”, as Noam Chomsky and other frontier thinkers have been calling our theme, or mind’s place in evolution as I prefer to see it, Kurt Vonnegut may have hit the nail on the head when he wrote:

“Tiger got to hunt, bird got to fly;

Man got to sit and wonder ‘why, why, why?’

Tiger got to sleep, bird got to land;

Man got to tell himself he understand.”

The homo sapiens must understand! That’s both his psychological need and his source of power. It’s only when he gives in to this need, and configures his pursuit of knowledge as the quest for that all too rewarding “Aha! experience” that affords it—and then holds onto what has afforded it and calls it “reality”—that this enormous source of power turns against him!

And solidifies into those “chains” that Rousseau warned us about!

You’ll comprehend reification well enough if you take into account that the mind evolved to help higher-order animals navigate the natural world (and not crash into trees or try to wrestle a tiger); and that we humans use it to navigate the human-made world. Reification makes us believe that human-made things (ideas and institutions) are in a similar way real (and hence immutable) as things in the natural world are (Bourdieu, Weber and other sociologists called this cognitive phenomenon doxa).

Reification becomes the foundation of society-and-culture when we reify “happiness” as the sensation “caused” by an event or an acquisition; and “freedom” as acting as we feel like. And when we take it for granted that “free competition”, “free market” and “free elections” really are free; and that “the pursuit of happiness” that’s been conceived in this way really leads to happiness.

Reification is most dangerous when we apply it to institutions; and consider them as “the reality” we have to live with—regardless of how obsolete and dysfunctional or downright absurd they may have become; when we conceive of “democracy” as “the government of the people, by the people, for the people”—and reify it as system of governance we happen to have; and when we consider “science” as the way to “objective truth”—and reify it as what the scientists are doing.

Reification is most insidious when we reify our social role; and think and act in accordance with a learned pattern—even while saying that this pattern has to change.

You’ll join this impending revolution of awareness (which is here prototyped as holotopia) the moment you say “no” to this debilitating kind of reification.

Our Situation

It will soon be a century since Benjamin Lee Whorf told us, in “Language, Truth and Reality”:

It needs but half an eye to see in these latter days that science, the Grand Revelator of modern Western culture, has reached, without having intended to, a frontier. Either it must bury its dead, close its ranks, and go forward into a landscape of increasing strangeness, replete with things shocking to a culture-trammelled understanding, or it must become, in Claude Houghton’s expressive phrase, the plagiarist of its own past.

Science must not become the plagiarist of its own past.

Let’s liberate science from “culture-trammelled understanding”! Let’s make it applicable to all questions that—now urgently—have to be answered.