The horrible fact is that democracy, and capitalism, will not solve those problems. We do need a fundamental paradigm shift in the area of governance.

– Jørgen Randers

Before I offer you an answer to this question, let me sum up briefly why we have to refocus our efforts from solving problems to shifting the prevailing societal-and-cultural order of things or paradigm as a whole; why we must make this seemingly obscure goal our most urgent and most cherished one.

1. Why Focus on the Paradigm

One of the reasons is that this is the most powerful—yet completely neglected—form of political action.

In Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System, Donella Meadows identified restoring “the power to transcend paradigms” as the most powerful way to intervene.

Another reason is that smaller interventions as a rule don’t—and cannot—work.

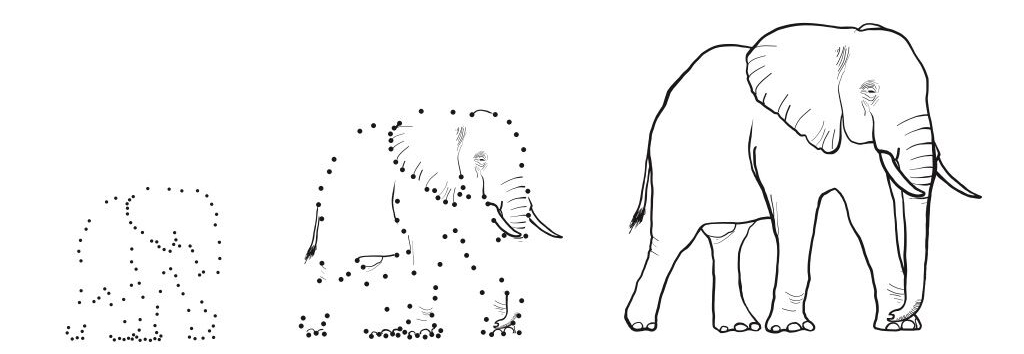

For a similar reason you cannot implant an elephant’s organ into a crocodile: Like an organism, a paradigm is a complex system where everything depends on everything else; like an organism, a paradigm rejects all that is extraneous to it.

An instructive historical example is The Limits to Growth report of The Club of Rome, which here has an iconic role; of which Donella Meadows was a co-author. Not only is our economy structured so that it must either grow or collapse; but our values too have been shaped by commercial interests, by shaping for us “the culture of wants”—as Adam Curtis showed in The Century of the Self.

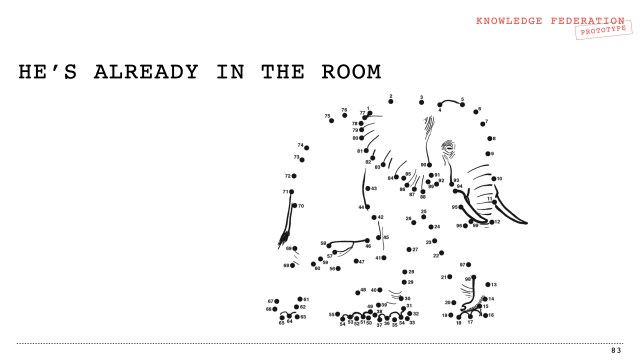

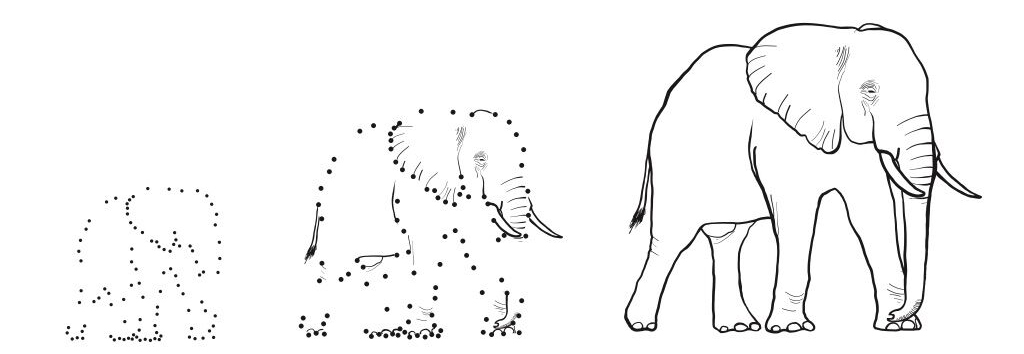

The third and main reason is that we own all the data points needed for a comprehensive paradigm shift; we only need to connect the dots.

And this all-important collective capability of ours (to make sense of the information we already own, and to act in accord with it), which will restore to function our “power to transcend paradigms”, is something we have to do anyway; for intrinsic or epistemic or academic reasons.

And so this most powerful way to intervene has a leverage point where it is easiest to intervene—our schools and universities; or the academy, as they are here called.

But let me illustrate these abstract ideas by a couple of real-life examples.

In the holotopia paradigm prototype, Jørgen Randers too is an icon.

His story begins around 1969, when Jørgen traveled from Oslo to Boston to do a doctorate in physics at the MIT; and ended up being a core member of The Club of Rome’s The Limits to Growth study; and a co-author of the corresponding book, and report.

Imagine that you were a gifted young man who has just realized that our civilization is headed to a disaster. What would you do?

Ten years ago I had the chance to hear Jørgen recount his history himself. At that point he was 70 years old; and retiring from his post as a professor, and former president, of the BI Norwegian Business School. A one-day conference was organized at BI to honor and celebrate this extraordinary man. Here is what he told us.

When The Limits to Growth book was published and publicized, Jørgen and Dennis Meadows did their very best to make the insights of the MIT study understood and acted on; and had to suffer through a series of completely nonsensical “debates”; the media called them “doomsday prophets”; critics often focused on the study’s “overshoot and collapse” scenarios, interpreting them as predictions of inevitable doom and dismissing the study’s overall message, Google’s AI summed up. (I’ll come back to this “overall message” in a moment.)

So Jørgen thought—OK, perhaps we just need to wait until the problems become visibly alarming; then people will listen. But he needed something to do meanwhile; so he became a BI president and professor. At some point he was asked by the Norwegian government to form a team and make a proposal—so that Norway could be part of the solution, and avoid being part of the problem. The proposal that resulted—because it included a small increase in taxes—was so politically inopportune that it was not even seriously considered.

You can see and hear a different version of this story: Following the fortieth anniversary of the publication of The Limits to Growth report, a documentary called Last Call was created; and it’s now on YouTube, along with its brilliant five-minute trailer. I recommend you this trailer because it contains two video excerpts that illustrate our public discourse as it is now (which our dialog must be able to thoroughly reconfigure). In one of them, you’ll see President Ronald Reagan say in a most alluring tone: “We believed then, and now, there are no limits to growth and human progress, when men and women are free to follow their dreams.” In the other, you’ll witness one of those so utterly futile “debates”.

This other, parallel vignette will help you comprehend the true (systemic) meaning and purpose, and message, of The Limits to Growth study.

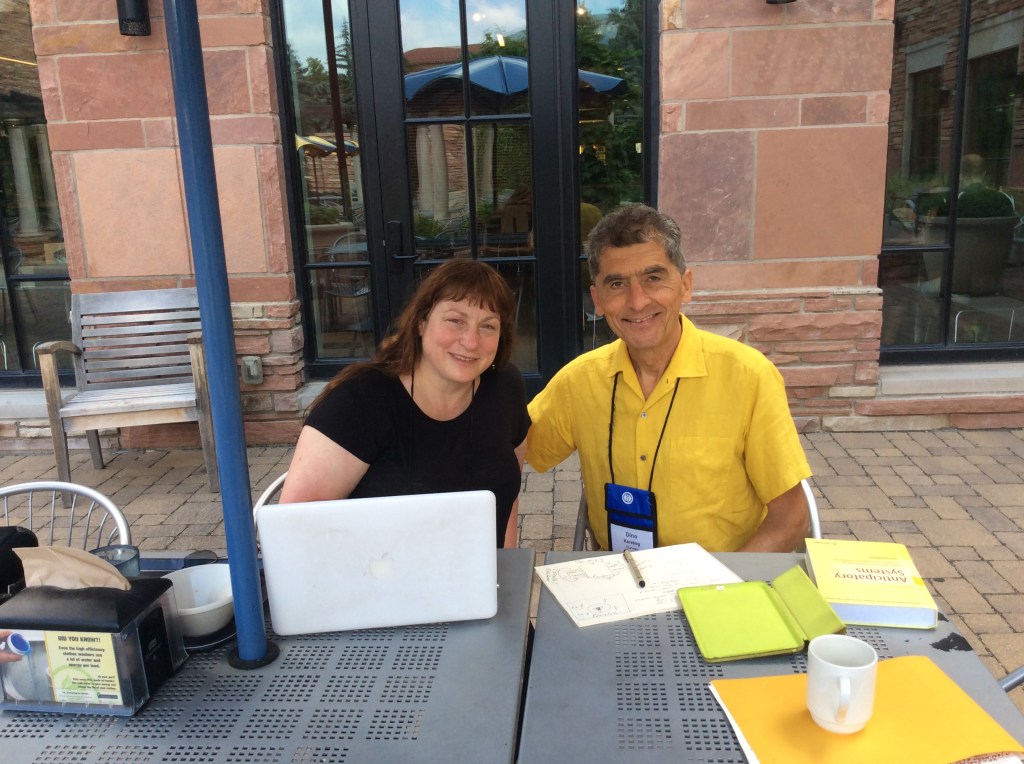

While on sabbatical at the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions in Santa Barbara, in 1972, mathematical biologist and systems scientist Robert Rosen observed that something crucial was still amiss in academic and popular conception of democracy. A book resulted, called Anticipatory Systems: Philosophical, Mathematical and Methodological Foundations; in which Rosen showed that all living systems—more precisely all systems capable of living, and the “sustainable” society or democracy in particular—are or must be “anticipatory”.

They must steer their course by making predictive models.

Our democratic institutions are distinctly (not anticipatory, but at their very best) reactive!

The above photo of Judith Rosen and myself was taken during the 60th yearly conference of the International Society for the Systems Sciences at the University of Colorado at Boulder campus. Judith and I skipped the early morning session, and I had the chance to hear also Robert Rosen‘s story first-hand. Judith—just like Christina Engelbart—is a dutiful daughter who knows that her father had a huge gift to the mankind, which has not been heard and accounted for. Both daughters are doing what they can to make a difference.

Judith gave me two gigabytes of text and lecture slides. I asked the waiter to take a photo; it’s knowledge federation in action.

“It has to be emphasized,” David Bohm observed in On Dialogue, “that as long as a paradox is treated as a problem, it can never be dissolved. On the contrary, the ‘problem’ can do nothing but grow and proliferate in ever-increasing confusion.”

The Limits to Growth study constituted a necessary update to the system of our “democracy”; necessary to make it “anticipatory”, and hence “sustainable”. What this study showed was that “democracy” lacks (not only ‘headlights’, but also) ‘brakes’. And on a still deeper level—we are “culturally unprepared” to even understand our new position clearly, as Aurelio Peccei diagnosed.

I enclosed “democracy” in double quotes because—as it is currently structured—our system of governance is not a “government of the people, by the people, for the people”.

It is a system that cannot be governed.

And it’s also a system that cannot update itself.

We vitally need a new process; which leads to structural change.

2. The Process I am Proposing

What I’m really proposing—and implementing with audience participation—is what Erich Jantsch called “the process of process”; and what he and Erwin Laszlo urged us to do:

To focus on evolution—and do whatever is needed so that the evolution of our society-and-culture can continue, and follow a good course.

Here I’ll remind you of our the modernity ideogram and our standard metaphor; where our society-and-culture is depicted as a bus with candle headlights.

And of the fact that no sequence of improvements of the candle will produce the lightbulb.

For all we know—the same may be said about our society-and-culture as a whole.

The process I am proposing (it subsumes the process of process as a special case) is to create a prototype and organize a transdiscipline or a dialog around it; to update it as needed—and to implement it, strategically, in real life.

The prototype provides us a shared vision.

Which is essential—if we are to coordinate our action toward a shared goal.

The holotopia paradigm prototype has already been created; and it includes coherent answers to all pertinent questions I can think of.

The next step I am proposing is to organize a dialog around it.

And the dialog is what Gregory Bateson called the “metalogue”: Its subject includes its own structure; our dialog needs to be able to address and answer also this question:

Do we need a prototype—to (organize ourselves in an impactful way and) be able to shift the paradigm?

If we answer it positively—or if you already agree that we need a prototype—I’ll urge you to self-organize together without delay and implement this strategy.

I will now supplement this strategy proposal with a vignette—describing how the holotopia paradigm prototype originated; not the whole thing, but only how it began to unfold. As vignettes tend to—this one too will provide us a multiplicity of clues; which I will then comment on briefly in this essay’s conclusion.

3. My Story in a Nutshell

Around the time when I was about to defend my doctorate, János Komlós, my advisor, showed me a page-and-a-half letter he received from Donald Knuth (esteemed as “the father of the analysis of algorithms”); where Knuth was urging János to accept the full professorship that was offered to him at the computer science department of Stanford University (which was then ranked as number one in that field); because Knuth himself wanted to work with him.

I am telling you this to suggest that the way of thinking or the meme that János here represents as an icon is indispensable for our task at hand; just as it was indispensable to Donald Knuth and the analysis of algorithms.

Right after graduating from university, I became a research assistant in an environmental systems modeling team of the Ruđer Bošković Institute in Zagreb; and had the chance to learn about systems science and systemic thinking.

The honor of being part of a prestigious institute weighed on me heavily: I had an enormous respect for science and learning; and I didn’t feel competent in my role. So I decided to do a doctorate at a good international university and start from scratch.

János was my third advisor; with the first two I observed that they were only pursuing a “publication record” and a career; and had to conclude this is not what I came here to learn.

Things were different in algorithm theory: It has “open problems”, and you had to solve some of those to prove your worth. Not long before we began to work together, János and his two friends solved a major open problem in algorithm theory; which Donald Knuth pointed to in a seminal book of his a decade earlier. Their result was profoundly complex; it introduced a technique that subsequently enabled a whole series of breakthroughs. (I should mention that to this trio of distinguished mathematicians this constituted a relatively minor achievement; one of them, Endre Szemerédi, later got the Abel Prize—the equivalent to Nobel Prize in mathematics; and also that the meme I am introducing through this story was not their invention—but something that just happened to be alive in the Alfréd Rényi Institute of Mathematics of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, from which they and quite a few other leading discrete mathematicians stepped out into the world.)

But the hero of this story is a meme, a different thinking.

I noticed that the way of thinking and working of these people was completely different from how I through a creative mind might operate. They all worked by taking long walks! During my many working walks with János, I realized that he didn’t think by trying to fit pieces together by trial and error (which you cannot really do while you walk; you’d be much better off using pencil and paper); but by condensing an intuitive image of the whole thing, through an entirely different process. I became interested in the phenomenology of creativity; and realized that many creative people (including Tesla and Einstein, as I reported in Transdisciplinarity Is a Way to Change Course) worked in that way; which is called direct creativity in the holotopia paradigm prototype.

So I endeavored to learn to be directly creative.

A metaphor from algorithm theory will help you comprehend the role of direct creativity, and of the holotopia paradigm prototype that resulted from its application, within this (quest for a) process whereby the paradigm can be changed.

There is a class of computational problems that are called “NP-complete”; which share a certain peculiar characteristic. The best known NP-complete problem is the so-called Traveling Salesman Problem, whose story definition reads as follows: A traveling salesman has to visit a large collection of cities each month; he has a roadmap, and knows the distance between each pair of cities; he wants to find the shortest possible way to visit each city exactly ones, and come back home. Suppose he knows a tour that’s 2000 kilometers long; is there a shorter one?

The point here is that finding an answer to this question is extremely hard and time consuming; it is practically speaking an impossibility; but if you are given an answer—it takes only a moment to verify that it is indeed an answer.

4. How the Process Needs to Unfold

I submit this to our dialog: In a similar vein, it would be extremely hard to demonstrate that there is an entirely different (sustainable, better, happier, healthier…) societal-and-cultural paradigm; which is ready to emerge in our midst because we already own all the data points needed to create it.

When, however, we have a prototype of this new paradigm—the task of comprehending it and verifying that it’s coherent and vital becomes incomparably easier.

An interesting question is whether direct creativity is necessary for the conception of a paradigm; whether trying to achieve that by fitting pieces together, by trial and error, would be rather like attempting to forge a solution to the Traveling Salesman Problem in this pedestrian way.