Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high; where knowledge is free; where the world has not been broken up into fragments of narrow domestic walls; where words come out from the depth of truth; where timeless striving stretches its arms toward perfection; where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way into the dreary sand of dead habit; where the mind is led forward by thee into ever-widening thought and action—into that heaven of freedom, my Father, let my country awake.

– Rabindranath Tagore

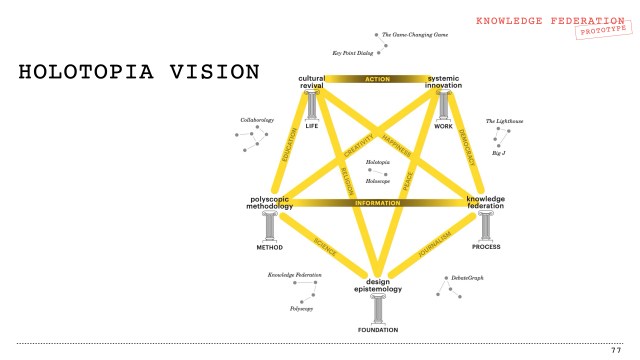

This blog post completes the presentation of the Holotopia initiative, which will be launched on October 18. Until then, this blog—its initial runway—will be under construction.

In 2012, at the fortieth anniversary of the publication of The Limits to Growth report at the Smithsonian in Washington, Jørgen Randers—a co-author of this still most widely read and cited book on environmental issues—diagnosed:

The horrible fact is that democracy, and capitalism, will not solve those problems. We do need a fundamental paradigm shift in the area of governance. So it’s the national and international governance [system] one ought to be debating, when one is looking ahead.

Did you notice the word “debating” in Jørgen’s call to action? It stands to reason that debating is not the kind of process that could ignite a fundamental paradigm shift in governance; or any other fundamental change. A moment of thought will suffice to see that we do not have any such process.

What is here called dialog is (the process of the creation of) this essential process by definition.

“Know thyself” has been the battle cry of sages through the ages. Yet there is something hugely important about ourselves we still ignore. Which—when seen and comprehended and acted on—will alter our civilization’s evolutionary course beyond recognition.

Will we do that before it’s too late?

This question motivates the Holotopia initiative; the dialog is conceived as a medium whereby we’ll co-create a positive answer.

If you’ve seen this blog’s About article, you’ll know that it is by fostering “new thinking”—which is here called logos—that the dialog has to begin; so that through logos (which is the meaning of the word dialog) we may comprehend things in new ways and act differently.

You will then also know that this “new thinking” is now demanded by academically reached and reported fundamental insights or “anomalies”—just as the case was four centuries ago, in Galilei’s time; and that it is through evidence-based self-reflection that the dialog must begin.

The founding fathers of Enlightenment took it for granted that God created the world as it is; and man “in his image”; and that the human mind is capable of perceiving and comprehending “reality” as it truly is. By depicting the legacy of the academic tradition as a road that ends at the mirror, the mirror ideogram points out that we can no longer pursue knowledge on the foundation they left us; neither can we continue to rely on the institutions that they created.

We begin the dialog by considering the mind as a product of natural evolution; and information as a product of societal-and-cultural evolution; and acknowledging that together they need to guide us to a new phase of our evolution; and adapting how we use them accordingly.

What is it, above all, that we need to learn about the human mind from the theory of evolution?

Here on the table in front of me is a rather thick book titled Deceit & Self-Deception. Its author, Robert Trivers, “is among the most influential evolutionary theorists alive today” according to Wikipedia.

Examples of deceit constitute some of the most spectacular, cloak-and-dagger pages of biology; and demonstrate that deceit is ubiquitous in nature; that it’s part and parcel of every species’ “evolutionary fitness”s. What Trivers undertook to demonstrate in this book is that self-deception is just as ubiquitous; and that self-deception too is an essential part of evolutionary fitness.

His main point—and that’s only one of the many ways in which we may come to the direction-changing insight I want to tell you about—is that the evolution has endowed the mind with the capacity to deceive itself.

The evolutionary fitness is thereby increased in two ways: By deceiving ourselves, Trivers emphasized on his book’s very title page, we become more capable to deceive others. And by allowing ourselves to be deceived by others—we become more capable of creating competitively stronger communities, and of playing our part in them.

Human cloak and dagger stories constitute a lion’s share of our history books; and of our media news.

But can this sort of evolution continue?

Logos vs. Habitus

Dialog is not just any conversation; and it doesn’t even have to be a conversation. Its meaning is as it was in Antiquity—through logos; we are in the dialog when we undertake to use evidence-based reflection to correct the way we comprehend things, and prioritize and direct action.

To truly comprehend the meaning of logos, its antonym habitus will prove useful.

I adopted it from Pierre Bourdieu; who used it to formulate his “theory of practice”, and explain how the society-and-culture really operates; and to theorize and explain the (still commonly ignored) renegade power that has thwarted humanity’s aspirations to knowledge and freedom; which we here call power structure. Many other points of evidence—notably the insights that Antonio Damasio reached through research in cognitive neuroscience, and published in a book called Descartes’ Error—have been assembled in the Holotopia book manuscript to elucidate the meaning of habitus; and demonstrate that habitus is the rule and logos an exception. It will, however, suffice for the purpose of this conversation about the dialog, to consider habitus as simply—the product of habit, or of habituation.

If habitus has provided the cohesive tissue for the historical societies-and-cultures to evolve—why should our evolution be different?

There are two reasons for that—and both are pointed to by the mirror ideogram. One of them is that fundamental insights compel us to ‘see ourselves’ and “know ourselves” in this new way and dispel self-deception. The other reason is that when we see ourselves in the mirror, we see ourselves in the world.

We then become aware that dispelling self-deception is the necessary condition for our continued existence.

The irony in our situation is that our society-and-culture—or more precisely the ecology of mind we are immersed in—makes the dialog all but impossible!

Here is how I attempted to point this out in the Holotopia book manuscript.

Once we’ll have learn to recognize habitus and distinguish it from logos—you’ll see that habitus is everywhere.

We’ll see it in the history and the present condition of the environmental movement, for instance.

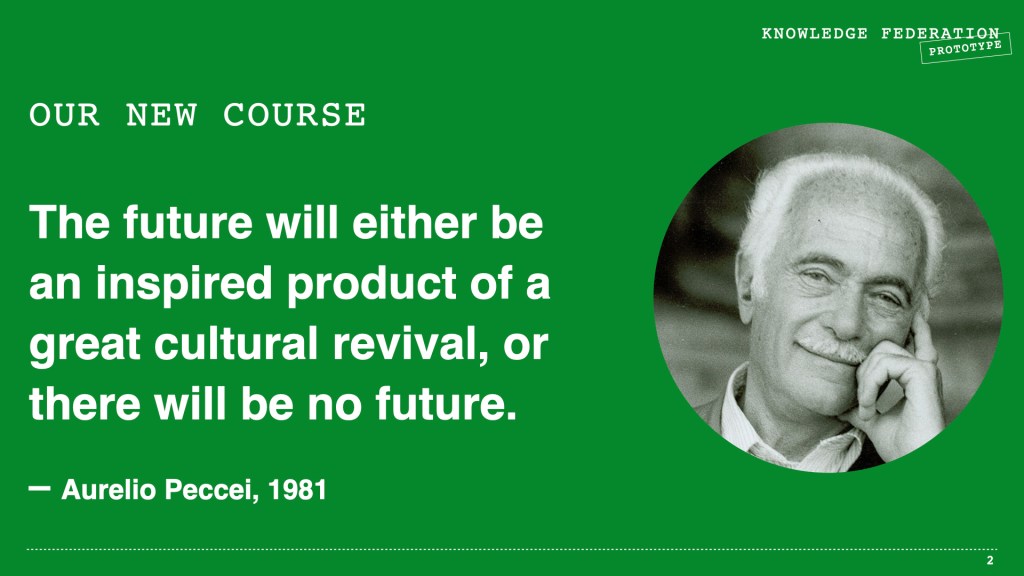

Here The Club of Rome, represented by Aurelio Peccei, its founding president, has an iconic role. Already at its point of inception, The Club of Rome decided to not focus on specific problems but on “the world problematique”—the underlying condition from which they all stem. And already in its first report—The Limits to Growth, in 1972 (which still today stands out as the most widely published and translated book on environmental issues)—The Club of Rome diagnosed that we must “find a way to change course”.

And yet still today a vast majority of people live in ignorance of this nature of our condition; while the vast majority of those who don’t—tend to focus on “problems” and ignore the “problematique”.

The Club of Rome struggled against habitus—to make themselves heard—but without success. This experience compelled Peccei to point to point to ethics and “cultural revival” as the strategic direction we need to focus on.

And to single out “the human quality” or “human development” as “the most important goal”.

We’ll also recognize habitus in the history and the present condition of religion.

Here Buddhadasa has the iconic role; for having first discovered that Buddhism has a phenomenology (a ‘law of nature’)—still widely ignored—as its point of origin; and then that all Great World Religions share the same essence. And for conceiving his project as the liberation of the human mind; and for framing its end result (not as “enlightenment”, as it is usual, but) as “seeing the world as it is”.

You’ll recognize habitus when you look at a U.S. dollar bill; and notice that it has “In God We Trust” inscription; and recall that Christ’s only violent act on record was to expel the money changes from the house of God. You’ll recognize it in the fact that we still call the Crusaders and the inquisitors “Christian”; despite the fact that they flagrantly ignored and violated what’s been written in the Book.

Have they not succeeded in fooling us—by successfully fooling themselves?

You’ll see the struggle of logos to prevail over habitus in Gandhi’s iconic example.

Gandhi called his method “satyagraha”—relentless, unswerving adherence to truth. Which Gandhi emphatically saw (not as India’s or his “interest”, but) as everyone’s and the humanity’s true aim.

Here is how I introduced Gandhi and his insight and method in the Holotopia manuscript.

You’ll see the struggle of logos to prevail over habitus also in the history of the academic tradition; and in its present-day condition.

Socrates had no other aim in mind when he conducted his dialoguess, than to awaken logos; and to demonstrate to his young students, and importantly to Plato, that habitus is what people normally use.

What Plato added was to use logos to synthesize general guiding ideas and ideals; and to provide them as an antidote to basing core or pivotal beliefs on habitus—which still prevails.

You’ll see that the possibility to recognize habitus and replace it by logos is what David Bohm meant when he wrote that “this notion of dialogue…suggests that there is some way out of our collective difficulties”; which is quoted as the opening remark on the Bohm Dialogue website—where the legacy of this all-important Bohm’s line of work is summarized.

Which our dialog will have to build on.

I became aware of habitus—and began to study it systematically—a couple of years after I embarked on my thirty years-long hero’s quest (which resulted in the holotopia prototype); when it began to yield results. I imagined a variety of responses (disbelief, enthusiasm, spirited conversations…)—but none of them materialized.

What I got instead was—silence.

Or—in those few occasions when I demanded a response, such as when I asked to form a research group, or when I applied for promotion—anger! The arguments that were meant to substantiate those angry responses had nothing to do with what I did or wrote; it was clear that the decision whether they were academic and meaningful was made before my proposal was considered.

It was in this way that I realized that it’s not the lack of ideas that hinders the academy’s and the society-and-culture’s evolution—but our inability to listen to new ideas.

As in the Twelve Steps of Alcoholic Anonymous, the first and necessary step of our dialog could be to admit that we—all of us, including us working for global change—are necessarily part of the problem.

As long as we live in a society-and-culture, we embody its habitus.

Isn’t that what enables us to function in a society-and-culture and communicate with its people?

And yet this is also what we’ll have to change—to be part of solution.

Dialog as a Revolution

The Visions of Possible Worlds conference, which was organized by the Faculty of Design of the Politecnico di Milano and the Triennale di Milano in 2003, invited its participants to propose visions of a sustainable or better world, which are “possible” or realizable. With consistency that surprised me, the presenters pointed in the direction that Aurelio Peccei asked us to focus on.

My presentation had only one slide.

With a drawing of a bus with candle headlights on the left, a drawing of a bus with lightbulbs as headlights on the right, and an arrow from the former to the letter.

I introduced my proposal as follows:

The vision I intended to share involved the change of focus from material production and consumption to humanistic and cultural pursuits and values—from which a change of design, and of everything else, naturally follows. But being here these two days I have been feeling that my vision had already become reality! One after another you’ve been depicting various facets of my vision more eloquently and more artistically than I’ll be able to (my background is not in art and design but in science and engineering). However I know—we all know—that the larger community does not yet share our vision. This here is an elect group; outside of these walls, the world has not yet changed. The people out there are still busy pursuing Industrial Age goals. So the question remains How can we make our visions possible or real? How can we spread it beyond these walls? As Chris Ryan said at the end of the session yesterday, we all agree what needs to happen; the question remains How to make it happen? It is this how that my lecture will be focused on. I want to propose to you a concrete strategy.

I explained that the bus in my slide represented our society or culture; that its headlights represented our information; and I proposed this strategy:

What we’ve been talking about these two days is a revolutionary change—first of all of consciousness and of values; and then, consequently, of design. What is the strategic object that every revolution must secure first? Suppose we were talking about an armed revolution; what is the building, the strategic object that a revolution must have under control?…It’s the TV station!…Please don’t misunderstand me. I am not inviting you to an armed revolution. Our revolution is a revolution of awareness. But if even an armed revolution must make sure that it has the information under control—should that not be even more true in a revolution of awareness? Yet we seem to have ignored information. Given a bit more time, I could show to you that information is now indeed in the hands of our enemy.

The function of the dialog is to produce and to be the information that can ignite a revolution.

And there is clearly a need and a market for such information (I am now wearing my venture cup hat).

The mainstream media news channels have become a scam!

Their function is increasingly to “fabricate consent”—as Noam Chomsky warned us.

On the ashes of the tradition of good journalism, an alternative news ecosystem emerged, created by online podcasters; where people like Jeffrey Sachs—who have been banned from mainstream media—have a chance to tell us how the things really are.

The reality we live in is disheartening.

Aaron Antonovsky here comes to mind; who identified, famously, “the sense of coherence” (viewing life as comprehensible, manageable, and meaningful) as the key factor of “salutogenesis” (creation of health). As the things are—truth in our world comes at the cost of the sense of coherence; which few of us are willing to pay; and (Antonovsky showed)—for comprehensible reasons.

But there is a third possibility—represented by holotopia dialog.

Where information is conceived (no longer as reporting about the world, and keeping us in an observer role, but) as a means to empower us to make a difference.

The holotopia dialog realizes Plato’s program: We create general insights; and (instead of basing what we think and do on habitus)—we use them to seek awareness and direct action.

Dialog as Media Design

When he fostered “media ecology”, Neil Postman undertook to develop a knowledge base for an informed or conscious use of knowledge media. Holotopia dialog is intended to put this timely task into practice; to foster a creative frontier—where we’ll develop new ways to use the media; where each dialog will be composed in the manner of a music score—and orchestrated by suitable media.

Where does the book medium fit in this emerging order of things? Or does it fit in?

In Amusing Ourselves to Death Postman pointed out that the book allowed us to process ideas at our own pace, by reflecting about them; which the “immersive” new media inhibit.

The Holotopia manuscript was created to enable this way of media use, and thinking; and to prime the holotopia dialog.

The manuscript is written as a collection of vignettes (catchy and insightful people-and-situation histories) each of which is a snapshot of the emerging paradigm.

Its readers are invited to process them by reflecting about them; and in this way enter into a dialog with the book, and with themselves.

At the same time—many of those vignettes can serve as hints and entry points to specific transformative themes; which can be developed in-depth in suitable dialogs—and explicated in new books or movies, or through a combination of media.

One of the functions of the dialog is to synthesize the core insights that compose the holotopia vision; which elevate us above the information jungle.

I’ve been contemplating a concrete format, and experimenting with it: We’ll assemble a team of, say, a couple of dozen highly competent and innovative people; to dialog in a Bohm’s circle about a specific transformative theme for about a week.The theme could be any of holotopia‘s five insights, or any other (examples are provided in Transdisciplinarity Is the Way to Change Course). And I don’t mean that we should sit and talk for days on end, on the contrary! The idea is to meet for a couple of hours after breakfast, and for an hour before dinner.

And to spend the rest of the time in nature walks and reflection.

Norway offers us suitable venues; I’ve been in conversation with the owners of one of them.

Another idea for a dialog format emerged while I was sailing off the Adriatic coast with a couple of friends.

They introduced me to Irena Meier.

A Croatia artist living in Switzerland; who owns a house and a piece of land, and in effect a bay, on a small island called Šćedro; near a larger island called Hvar.

Irena created about a dozen dialog spaces in and around her house!

Some of which are large, and some of which are cosy.

She took me to a nearby chapel in ruin—which too might provide a powerful stage, for dialoging about a suitable theme.

When I told Irena my idea—she accepted it as if she’d just been waiting for it.

I presented it as a redesign of the conventional “reality show” format.

But please don’t take me wrong: This is a real reality show! Where we’ll have a suitable mix of protagonists, staying together for several days and dialoging —in different constellations—in front of the camera; about the world and its condition, and Holotopia as strategic initiative.

The point will be to give voice to distinct perceptions of core contemporary themes.

And see how habitus inhibits change; and witness how people share and transform their worldviews, by interacting with each another.

In the late 1990s, when all this was still only taking shape, I drafted a sketch of a book manuscript titled What’s Going On? And subtitled “A Cultural Renewal”. The idea was to answer the title question in an entirely different way than what’s become usual.

And instead of a succession of snapshots of spectacular events that happened that day—offer a portrait of a slow and much larger development; which gives meaning to specific events.

And offers a strategic direction to our efforts. I mention it here to point to this function of the holotopia dialog:

To provide us meaning, and guidance, in this time of need.

Dialog as an Art Form

It’s enough to bring to mind the Renaissance—and Botticelli and Michelangelo as icons—to realize that the next cultural revival too will need to be (also) an art project.

As I explained in Transdisciplinarity Is a Way to Change Course—Vibeke Jensen has been an icon of this line of work in the holotopia prototype.

Here is how I introduced her in the Holotopia book manuscript.