It is important to understand the quest for knowledge as a form of interaction between living systems and their environment, no less essential than, say, breathing or feeding.…The dissection into disciplines is possible only by sacrificing these live relationships between a knowledge-acquiring system and its environment—by stopping its mental metabolism, as we may also put it.

– Erich Jantsch

Like the rest of this blog, this blog post is work in progress. I am publishing them prematurely to ignite the self-organizing process through which we’ll become capable of changing the dominant paradigm; by co-creating this blog to begin with.

Instituting a transdisciplinary academy is here shown to be the key step in a process—by which our quest for knowledge is to be reconceived and thoroughly reconfigured. The process as a whole, and this key step in particular, are made concrete and actionable by the knowledge federation prototype—which comprises a complete and functioning model of a transdisciplinary academy, and its proof-of-concept applications.

This blog’s About article and three blog posts that precede this one constitute a case or an argument for instituting a transdisciplinary academy; which I will here only summarize—and then propose an action plan.

While reading this summary and call to action, it is important to bear in mind that this is not a statement of fact (with which you may either agree or disagree) but a part of a process; and that I am inviting you to have an active role in that process, by thinking and acting in a new way.

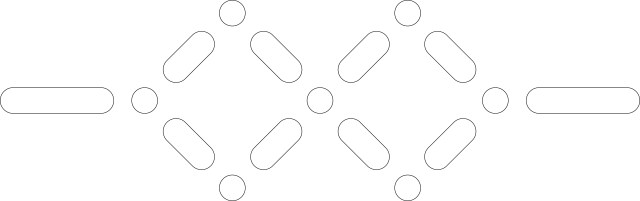

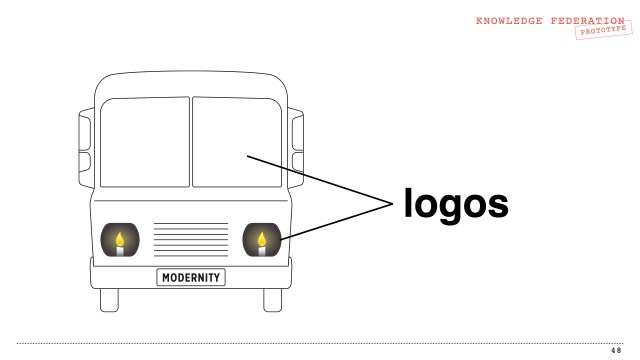

Throughout the knowledge federation prototype, this metaphorical image called modernity ideogram—where modernity (our post-traditional society-ad-culture) is depicted as a modern bus, and our information (which by definition includes both the artifacts such as academic articles and TV news, and the socio-technical systems and processes by which information is created and put to use) as its candle headlights—has been used to delineate the reconception and reconfiguration of our quest for knowledge.

Which is the aim of the process I am inviting you to be part of.

This summary of the case for instituting a transdisciplinary academy will be in two parts:

- The epistemological argument will show that the very working principle of our information is obsolete; and that this is what keeps modernity on its self-destructive course

- The technological argument will point out that the reconception and reconfiguration of information are necessary if we are to use the new information technology correctly; or in the language of the mentioned metaphor—that we’ve been using the electrical technology to create fancy candles.

Together, these two arguments will demonstrate that instituting academic transdisciplinarity is the key step in what is here called holotopia strategy—where (instead of only focusing on specific “global” and other “problems”) we endeavor to enable our present societal-and-cultural order of things or paradigm to change; and in that way become capable of handling—beneficially and safely—the immense power we’ve acquired through science and technology.

Epistemological Argument

Part of our problem is that the assumptions that underlie our quest for knowledge, and the working principle of our information, have not been written up and agreed on; they are simply taken for granted. If we were to spell them out, we would see that a “reality picture”—believed to pre-exist “objectively”—is at their core. In the sciences, this is reflected as the quest for explanations—whereby the observed phenomena are made comprehensible to the human mind; in public informing, this is reflected by the news conceived as snapshots of real-life events. The underlying assumption seems to be that the conclusions that a normal human mind can draw from the “reality picture” by thinking “logically”—together with the “reality picture” itself—constitute all “truth” by definition; and that this “truth” is what what distinguishes (true) knowledge from (erroneous) belief.

The above mirror ideogram points to the fact that the scientists have “discovered” that there is no “objective reality”; that what we call “reality” is constructed—by our minds, and by our societies-and-cultures.

A moment of thought will suffice to see that this constitutes a logical conclusion of the paradigm I’ve just described.

When we see ourselves in the mirror, we see ourselves in the world.

The emerging paradigm—which is the subject of this proposal—unfolds when we see information as a human-made thing for human purposes; and undertake to handle it as we handle other man-made things—by adapting it to the functions it needs to serve.

The value matrix based on which we prioritize and evaluate information is thereby thoroughly changed.

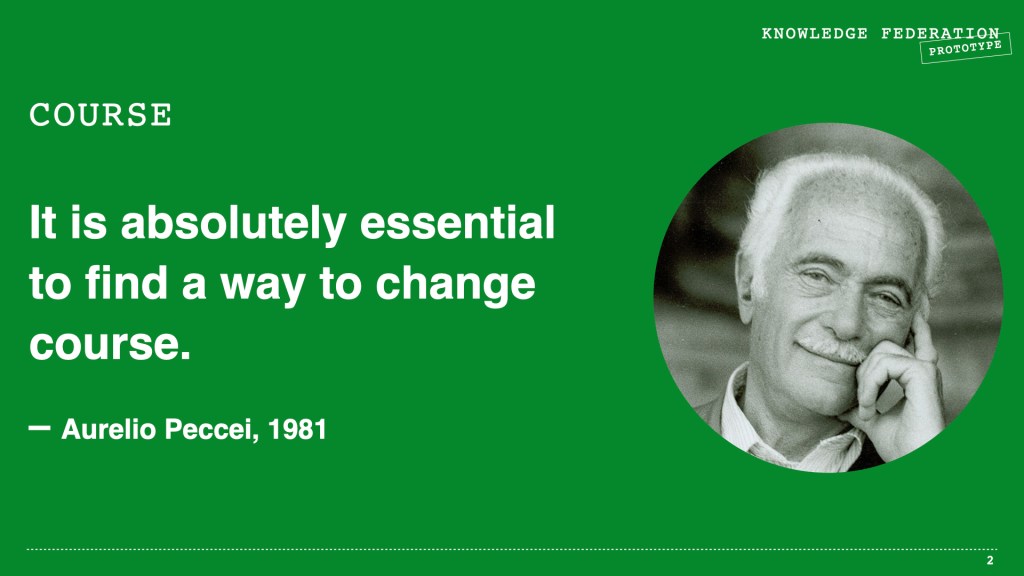

Aurelio Peccei warned, based on a decade of The Club of Rome’s research:

[T]here is no doubt in my mind that the human race is hurtling toward disaster, and that it is absolutely essential to find a way to change course.

Instead of struggling to complete a “reality picture”—we refocus our creative efforts on comprehending and handling the pivotal themes (the ones on which our ability to change modernity‘s devolutionary course depends).

“Truth” is then conceived (no longer as “correspondence with reality”, but) as creditability—which is here used to delineate “what is both reliable and collectively relied on”; constructing a way to comprehend and handle pivotal themes in creditable ways becomes the focus of new “basic research”.

This now well-defined challenge can then be handled in a natural way—by thinking and acting as we would do while creating a suitable pair of headlights for a passenger vehicle.

We’ll trust our information for reasons similar to the ones that make us rely on the automobile in which we drive our children to school.

The founding fathers of Enlightenment, and of the scientific revolution, lived in a worldview where God created the world as it is; and the man “in his own image”; from which the belief that the human mind can know reality followed. This proposal and call to action may be understood as a timely update—whereby evolution is added to this age-old worldview.

Where we see the human mind as a product of natural evolution; and information as a product of societal-and-cultural evolution; and acknowledge that together they need to guide us through the evolutionary dire straits we are in.

Logos—which has been seminal to academy—can now be reconceived as the way to use the mind and information as it may best serve that all-important function.

How should logos be different?

We can now answer that question by proceeding as we would do while creating the lightbulb, or any other human-made thing:

By identifying the design challenges; and the ideas and technical solutions that need to be adapted and combined to handle them correctly; or in a word—by federating knowledge.

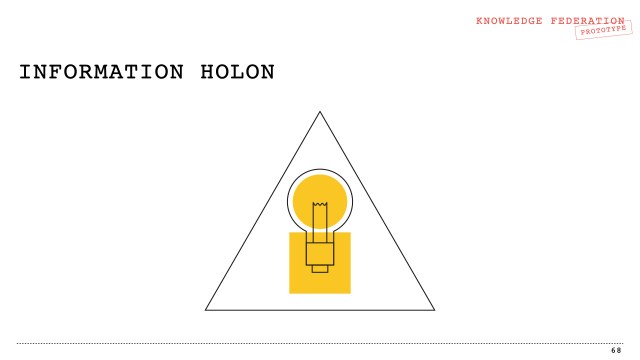

The object-oriented methodology—which revolutionized computer programming (Dahl and Nygaard got the Turing Award for creating it)—is here iconic, because of its two key idea; and its groundbreaking technical solution, which gave this methodology its name.

The first idea is to apply logos to method, and create a methodology.

So that instead of “the scientific method” (which seems to have been “discovered”; and to continue to exist “objectively”)—we may continue to evolve our quest for knowledge; by combining state-of-the-art insights and techniques. The polyscopic methodology constitutes a prototype of this approach.

The second idea is to tackle complexity by using abstraction.

Google’s AI summed this up:

Object-oriented programming uses encapsulation to hide internal details and expose only necessary functionality through an interface.

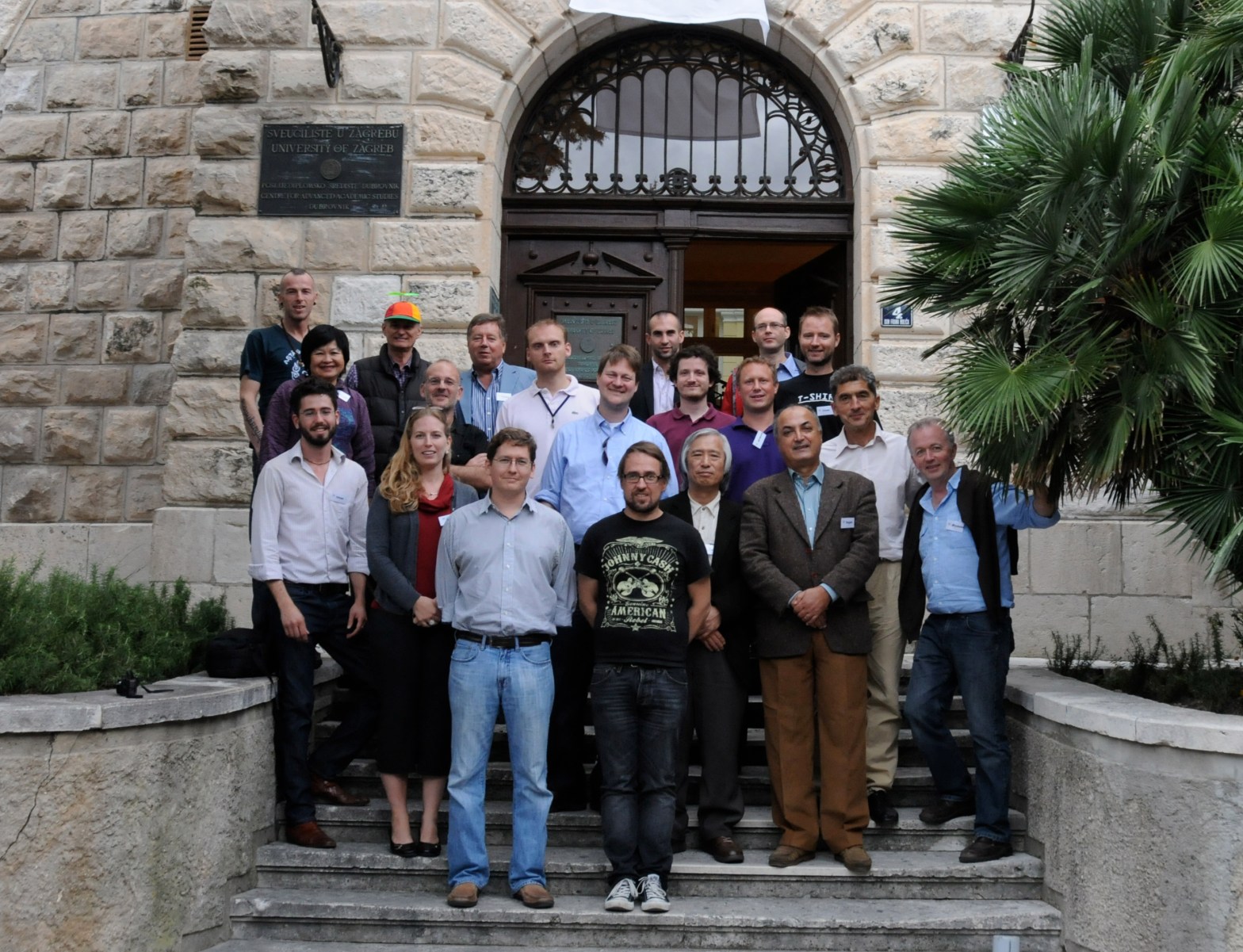

In a like manner, the information holon (represented by the “i” in the above information ideogram) of polyscopic methodology uses encapsulation to hide evidence from a multiplicity of sources in its square; and exposes the point of it all in its circle.

We use knowledge federation as keyword in a similar way as “design” and “architecture” tend to be used—to denote both a technology-enabled social process, and the academic field that develops it as praxis. It should go without saying that the traditional academic discipline would not be suitable for developing the praxis (informed practice) of knowledge federation; so we developed for a new institution, and called it transdiscipline.

The function of a discipline is to create information in its domain of interest; the function of a transdiscipline is (to combine heterogeneous resources together and) give to information relevance, and impact.

We use ideograms to communicate the most relevant points. The ideograms featured in the current version of the knowledge federation prototype are only placeholders—for a variety of media-enabled techniques that will be developed.

The ideograms also serve as boundary objects—and connect together two (now separate) domains of interest and ways of working.

For a couple of decades, Fredrik Eive Refsli—a profusely gifted young designer—and I have been working together in this way; where I organize the supporting evidence in a square, and he produces the circle. I may make a rough sketch of an ideogram.

But this is where science ends—and art and design take over.

By becoming transdisciplinary, the academy gives the holoscope to society; not only the telescope and the microscope, and other such things.

This enables us the people to comprehend and handle any theme or issue correctly, evidence-based.

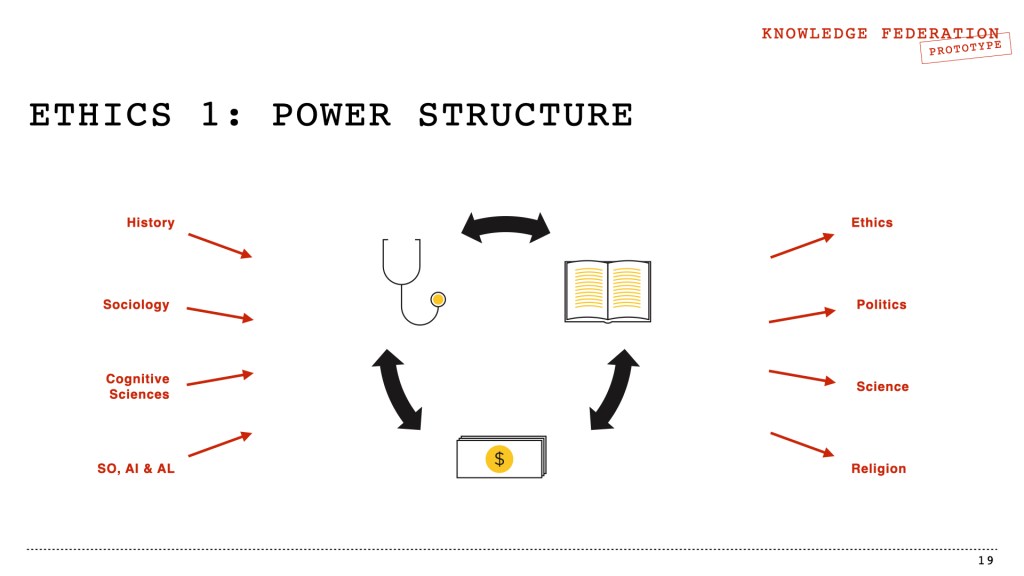

The power structure theory is a proof-of-concept application of the holoscope.

The microscope enabled us to see and study the germs; and to diagnose the infectious diseases.

The holoscope enables us to comprehend and diagnose the power structure—as a mortal yet curable societal-and-cultural ‘disease’.

A consequence of the power structure theory is to identify “free competition” as a ‘disease cause’ (emergence in complex systems is used instead of causality in this theory’s construction).

A radical change of ethics and politics follows.

When we use the holoscope as ‘headlights’—we see the holotopia; which is a comprehensively different and in its core dimensions radically better societal-and-cultural order of things or paradigm.

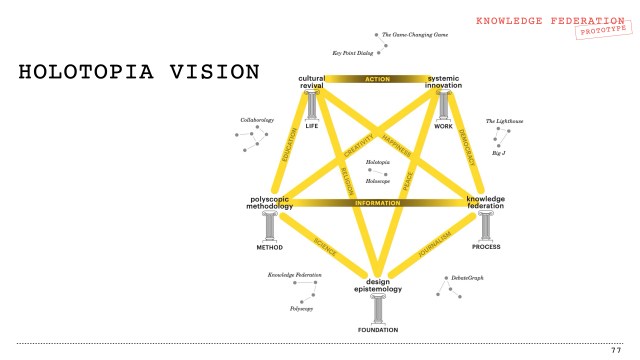

The holotopia vision resulted when polyscopic methodology was applied to five pivotal categories—which resulted in five insights, represented by the five pillars in the ideogram; whereby the conventional comprehension of the category inscribed under each pillar’s base is thoroughly changed, and its handling reversed.

And when other pivotal themes (represented by the yellow lines in this ideogram) are considered in the context of the five insights—their comprehension and handling too is similarly transformed.

On the cover of the Holotopia book manuscript the power structure is depicted as Max Weber’s iron cage. This book’s function is to prime and ignite the holotopia dialog; whereby we’ll liberate ourselves from the power structure and aspire to holotopia.

Google’s AI summed up Weber’s message:

Max Weber’s concept of the “iron cage” is a metaphor describing the restrictive nature of modern, rationalized society. It suggests that individuals become trapped by the very structures designed for efficiency and control, such as bureaucracy, losing their autonomy and creativity. This “cage” is characterized by an overemphasis on instrumental rationality, where actions are primarily judged by their efficiency and calculation, rather than by broader values or personal meaning.

Weber published The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism more than a century ago; and it is still today a required text for students in the social sciences; and yet its core message has not been integrated in our conventional thinking and worldview, and ethics and politics.

We need transdisciplinarity to take advantage of the insights that have been reached in the sciences; and comprehend the deep, societal-and-cultural roots of our problems; and to then draft a way to solutions—by federating a vision.

In Autobiographical Notes Einstein listed the great successes of science that followed from Newton’s theory; and then summarized the ensuing anomalies — which could not be handled by this theory; and concluded:

Enough of this. Newton, forgive me; you found the only way which, in your age, was just about possible for a man of highest thought and creative power. The concepts, which you created, are even today still guiding our thinking in physics, although we now know that they will have to be replaced by others farther removed from the sphere of immediate experience, if we aim at a profounder understanding of relationships.

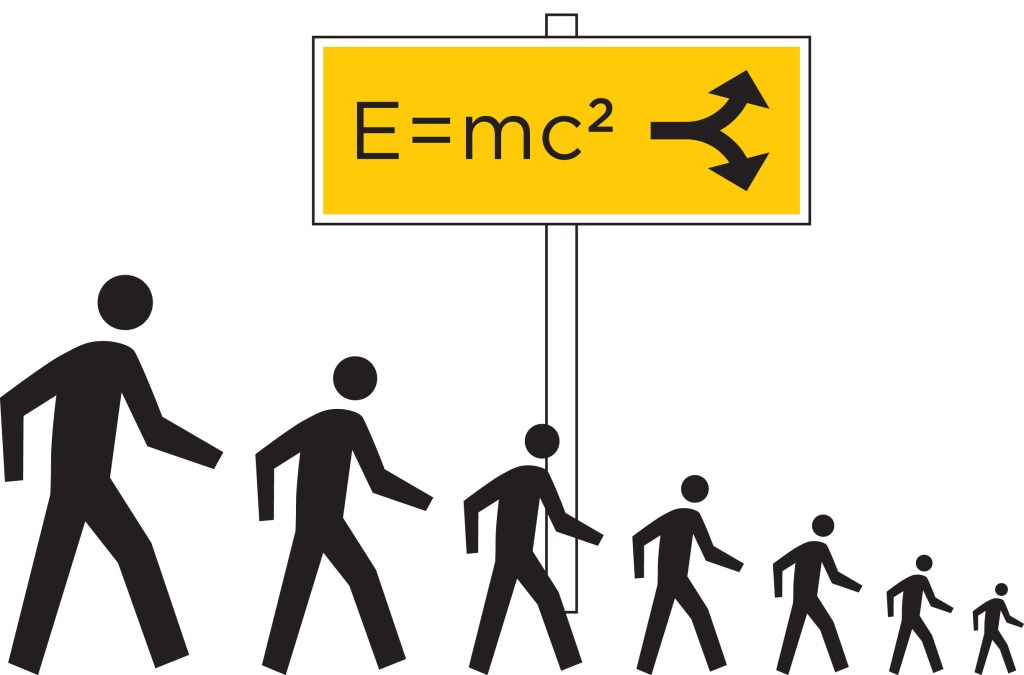

This science on a crossroads ideogram depicts the situation that resulted: When it was understood that Newton’s concepts were his own creation, and that his theories were only an approximation—two ways to evolve opened up to science. One of them was to grow science downward—toward greater precision and detail.

The other was to do as Newton did in physics in all walks of life—and create concepts, and approximate theories; grow science sideways, and upward.

Only the first of those options was followed; and science and scientists grew smaller.

The academy was created—by Plato, twenty-four centuries ago—in response to a similar situation in Athens as what we have today: Its Golden Age was over, its politicians’ ethics in decline and its democracy increasingly dysfunctional.

While we believed that “the nature of reality” was to decide what information was to be like—it seemed natural to consider the material things that we can touch see as more real than ideas. When, however, we conceive of information as the guiding light—it becomes transparent that “objective descriptions” of the world can only help us adapt to the world, that they cannot tell us how to change it.

And that we need general and abstract ideas and ideals to be able to correct the deception of the senses.

Plato created the academy to grow information upward; and to create creditable insights to guide us in ethics and politics.

After twenty-four centuries, we are finally able to heed his call.

Technological Argument

A technological development gave impetus to the last comprehensive paradigm shift (which here serves as a template for comprehending the ongoing one): Initially used to mass-produce the Bible—and automate what the monastery scribes were doing—Gutenberg’s invention ended up enabling the dissemination of new kids of knowledge; and spearheading the Enlightenment.

Its contemporary counterpart—the interactive, network-interconnected digital media, which you and I are using to communicate through this blog—is already in place.

But it’s still largely used to streamline the processes that the printing press enabled (of which academic publishing is an example).

What difference will this new medium make in the impending revolution?

In the knowledge federation prototype—where everyone is an icon and everything is a placeholder—this historical PowerPoint slide points to the iconic person and story whereby I’ll answer the rhetorical question just asked. The event for which this slide was prepared (but not shown) was intended to be the presentation of Engelbart’s vision, and to issue the call to action to implement his vision, at Google in 2007.

By the late 1990s it was understood that it was Doug Engelbart—and not Bill Gates, Steve Jobs and Tim Berners-Lee—who invented the mentioned technology; and he received a complete collection of medals and honors that could be awarded to a technologist. Yet it was also known that Engelbart considered himself misunderstood, and celebrated for wrong reasons.

The long in the short is that Engelbart envisioned—and prototyped with his Stanford Research Institute-based lab, and showed to the world in his celebrated 1968 Demo—the ‘electrical technology’ required for creating the ‘socio-technical lightbulb’.

To comprehend the new thinking that Engelbart pointed to in his Slide 1, and how it bears upon our task at hand (to institute a transdisciplinary academy) a parallel ‘Galilei in house arrest’ story might be helpful. Its context is The Club of Rome as the iconic attempt to federate—and to be—modernity‘s ‘headlights’ (and show us where we are headed, and how to change course). Its iconic hero is Erich Jantsch—who gave the opening keynote at The Club of Rome’s inaugural 1968 meeting in Rome; and instantly saw what had to be done—if we were to become capable of changing course.

Right away Jantsch organized a workshop of hand-picked combination of thought leaders, to foster the praxis of “systemic innovation”.

Jantsch then spent a semester at the MIT, drafting a plan for a “transdisciplinary university”—as the institution that would be capable of spearheading systemic innovation; he lobbied with the MIT administration and academic colleagues, for this leading technological university to become the leader in this all-important trend.

In his MIT report Jantsch pinpointed the requisite new thinking:

The task is nothing less than to build a new society and new institutions for it.

Before we’ve self-reflected in front of the mirror (and learned to see ourselves as the creators of society-and-culture, not as its “objective observers”), it seemed to be our only option to see the systems in which we live and work as the “reality” we just have to live with and adapt to. On the other side of the mirror (in the emerging paradigm) we’ll see them as just another kind of things that we the people create for human purposes; and we’ll realize how much they have been transformed and thwarted by the power structure; or more practically speaking—to what stupefying degree the way we live, and the institutions that determine the effects of what we do, have been shaped (not by conscious intents to improve our lives, or to make our good efforts serve a good purpose, but) by competing, narrowly-conceived “interests”.

To see the creative frontier that’s emerging, which systemic innovation here stands for, consider how smart is your smartphone; and how much our media news and our scientific communication are devoid of any purposeful design.

And if our systems of information are so unintelligent—why should our democracy, our corporations and our financial system be any better?

Erich Jantsch wrote in his MIT report, in the continuation of the just-quoted excerpt:

With technology having become the most powerful change agent in our society, decisive battles will be won or lost by the measure of how seriously we take the challenge of restructuring the ‘joint systems’ of society and technology.

Although during the 1070s Jantsch was just about Engelbart’s neighbor (he lived in Berkeley and conducted seminars at U.C. Berkeley)—he didn’t seem to be aware that Engelbart created exactly what he was calling for:

The enabling technology for a quantum leap in the evolution of humanity’s systems.

In a futile (lifelong) attempt to make his core idea comprehensible to the Silicon Valley’s academics and developers, Engelbart branded it as “augmenting our collective IQ” (and defined “collective IQ” as our collective capability to cope with the complexity and urgency of our problems; which he saw as growing at an accelerated rate or “exponentially”). But on a closer look we see that his intention—and achievement—were larger. As Norbert Wiener observed in Cybernetics—information is what combines autonomous individuals into a system; information is the system! Engelbart even created an ingenious method for systemic innovation; and published it as an SRI report in 1962—six years before Jantsch and his team would meat in Bellagio, Italy, around that timely goal.

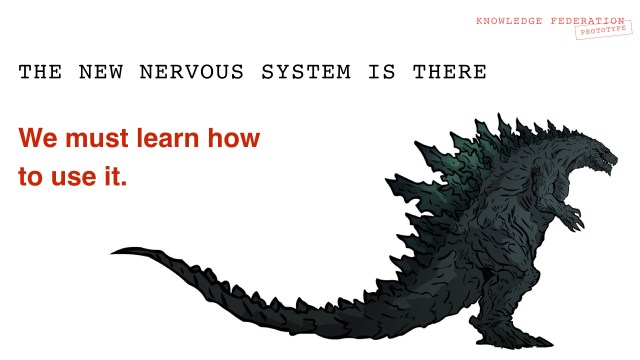

When I taught the Douglas Engelbart’s Unfinished Revolution doctoral course at the University of Oslo (to make Engelbart’s legacy comprehensible to future IT researchers, and to research it thoroughly myself)—I used to sum up the gist of it by commenting on the above slide. Just like this creature, I would tell my students, our civilization has grown powerful and large beyond measure; its uncoordinated reptilian actions are now a threat to its environment, and to itself. Fortunately, this creature has recently developed a new nervous system—which will enable it to make an evolutionary quantum leap in awareness.

But it’s still lacking a process by which its mind and mindset can be updated.

It is that process I am inviting you to be part of.

The Knowledge Federation community was fostered in 2008, by a small international team of researchers developing technology-enabled systems for collaborative knowledge work. We readily saw that the technologies and systems that we and our colleagues were developing was positioned to transform our information (or collective mind), and our socio-technical systems in general.

What was still lacking was a socio-technical system capable of doing that job (systemic innovation).

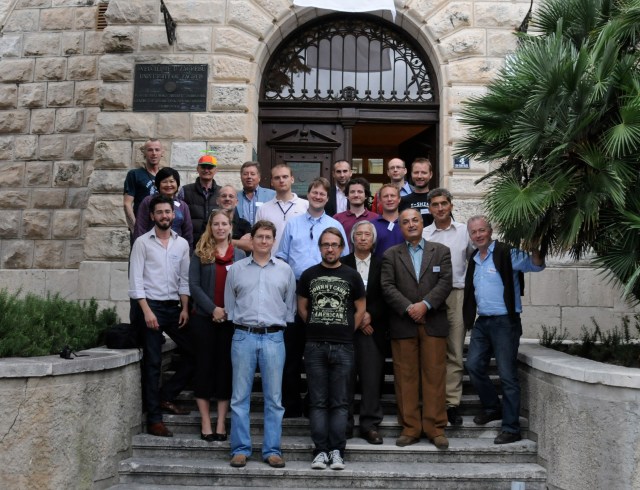

So we decided to organize ourselves differently—and become that system. To our next biennial workshop in Dubrovnik, in 2010—which we named “Self-organizing Collective Mind”—we invited frontier thinkers in a suitable combination of professions, including journalism, open science and communication design; and asked them to self-organize in a manner that would enable further self-organization. The result was a new prototype—of the knowledge federation transdiscipline.

In 2011, at our workshop at Stanford University, which we organized within the larger international Triple Helix IX Conference, we announced systemic innovation as a necessary and emerging trend; and the institutional structure and way of working represented by the knowledge federation transdiscipline as its enabler.

Here is how this new system operates:

We organize a transdisciplinary community around the challenge to create a system prototype—and to implement it in practice, and secure its continued evolution, growth and impact.

Several months after we met in Palo Alto, at our workshop in Barcelona, we created a proof-of-concept application of this method, by applying it to public informing or journalism.

Let us pause and give you a chance to connect the dots.

When we see that the devolution of our systems (or in other words the evolution of power structure) is the root of our problems—we realize that systemic innovation must be their solution.

What you are witnessing—what you are invited to be part of—is the nascence of systemic innovation as our new collective capability.

At our workshop in Barcelona, (instead of letting our public informing evolve through competition of commercial and other narrowly-perceived “interests”) we asked:

What does public informing need to be like—if we the people and our democracy are to become capable of resolving “the huge problems now confronting us” (as Margaret Mead called them)?

The public informing prototype we drafted in Barcelona empowers the people and the democracy to comprehend the systemic causes of perceived problems; and to see and to pursue their systemic solutions.

Subsequent experience with this prototype revealed an error in the systemic innovation process we created: Following our workshop, the creative leaders in journalism we collaborated with got busy with their schedules; and it proved impossible to implement the prototype in real-life practice, and secure its continued evolution, growth and impact.

In this way we realized that the people who are in positions of power within a system cannot change their system—because they are too busy running it!

What they, however, can and have to do—is to empower the next generation professionals to implement the new system with their own minds and bodies.

In 2012, at our subsequent workshop in Palo Alto, we created a prototype called the game-changing game—of a system where the Z-players, who are in power positions within a system (as academic advisers, or investors) empower the A-players (who might be graduate students, or entrepreneurs) to ‘play their life-and-career games’ by transforming a system. We then met in Zagreb to foster The Club of Zagreb prototype—a reconception of The Club of Rome, whose workflow does not end with diagnosing negative trends and problems, and recommending their “solutions” (which as a rule cannot be implemented within the existing systems or power structure); but continues to forge the systems that enable, and are real solutions—through the game-changing game.

From Zagreb, with six A-players we moved on to our next workshop in Dubrovnik—where we began to draft the collaborology prototype; which implements the game-changing game in education.

Are you still able to connect the dots?

What you are witnessing—what you are invited to be part of—is the nascence of a transdisciplinary academy; which will be capable of guiding us the people through this precarious phase of our evolution; which will empower us to comprehend the roots of our problems—and forge real solutions.

Systemic innovation (as it’s been modeled and implemented within the knowledge federation prototype) is (a necessary part of) the real solution; but is it academic?

To make a case for instituting it as an academic praxis, we need to demonstrate that it truly is a body of knowledge that is worthy of being academically taught, and developed further. Did knowledge federation make sure to federate its own body of knowledge and methods?

What are the academic underpinnings of systemic innovation?

Clearly, they must include both the legacy of the research in knowledge media, and the relevant elements of the systems sciences; which, you may have noticed, are here iconized by Doug Engelbart and Erich Jantsch.

It was a most fruitful serendipity that Louis Klein—an elder in the International Society for the Systems Sciences, whose job description reads pretty much “systemic innovation in practice”—came to my presentation of the game-changing game at the Future Salon in Palo Alto. And approached me when it was finished, and said “I’ll introduce you to some people”. He introduced me to Alexander Laszlo and his team.

At that point the ISSS was having their yearly conference in San Hose; where Alexander was inaugurated as the society’s incoming president.

Alexander has Erich Jantsch as his personal icon, just as Doug Engelbart is mine. His father, Ervin Laszlo, was a prominent member of The Club of Rome, who created The Club of Budapest as its update—to include the work on ethical and cultural transformation. Alexander’s doctoral advisor was Hasan Özbekhan—who produced the first theory of systemic innovation at that historical workshop that Jantsch organized in Bellagio; and also wrote the original statement of purpose for The Club of Rome. Part of Alexander’s mandate as president was to organize the society’s next yearly conference in Haiphong, Vietnam.

This conference took place less than two weeks after Doug Engelbart died; and was conceived as an implementation of his vision: The ISSS was to become the first academic community to self-organize, with the help of technology, and become “collectively intelligent”; and help the larger community to self-organize, and become collectively intelligent. The conference that Alexander created was distinctly transdisciplinary; it even included a team of social entrepreneurs—who were to bring its transformative memes into the society.

This photo of Alexander and myself—taken in 2014, at the European Meetings on Cybernetics and Systems Research event in Vienna—is intended to be used ideographically.

To portray the transformative meme we now need to foster; whose nascence I am inviting you to be part of.

We are once again facing that metaphorical mirror; which is inviting us to step out of the “objective observer” self-identity; and encouraging us to self-organize differently.

“Be the systems you want to see in the world” is the slogan that Alexander chose for that conference in Haiphong; which was then also adopted as the slogan for the EMCSR event in Vienna.

It is also the gist of Engelbart’s call to action—which he undertook to issue at the mentioned event at Google, in 2007.

In 2016 Alexander created a doctoral program called Leadership of Systemic Innovation at the Buenos Aires Institute of Technology; and invited me to teach a class, and to give the opening keynote.

I told a variant of the Doug Engelbart history as springboard story.

Which allowed me to conclude:

Many countries have attempted to import the Silicon Valley’s entrepreneurial culture, largely without success. Now you may see that something much larger is possible; which the Silicon Valley was unable to implement—owing to the idiosyncrasies of its culture.

IUC Dubrovnik as Central Hub

The knowledge federation prototype includes a complete prototype of a transdisciplinary academy—ready to be examined and instituted, in a manner that will allow it to evolve further, and grow and have impact.

While this institution could be done in a number of ways—this concrete proposal is offered as part of the knowledge federation prototype. We are proposing to

- Institute a transdisciplinary academy at the at the Inter University Centre Dubrovnik

- Under the auspices of the World Academy of Art and Science

- And to work together toward its global growth by offering the collaborology course to the IUC member institutions.

The Inter University Center Dubrovnik was established by Croatian physicist, philosopher and author Dr. Ivan Supek, in 1970, to serve as a place where scientists and humanists from both sides of the Iron Curtain could meet and collaborate. At the onset of his career, Supek was Werner Heisenberg’s assistant; his uncompromising anti-war and humanistic stance marked his career’s subsequent unfolding.

As an inter-university organization, which includes the world’s leading universities as members, the IUC Dubrovnik is positioned to make transdisciplinarity available to self-selected next-generation talents worldwide.

The above photo of the participants of our 2010, where we began to self-organize as a transdiscipline, was taken at the entrance to the IUC Dubrovnik. And Dubrovnik happens to be my birth town.

I also have personal ties to Dr. Ivan Supek and to (IUC) Dubrovnik (in addition to similarities of interests and vision): My first job was at the Ruđer Bošković Institute, which Supek created; Dubrovnik was my birth town.

Here is how I explained why the IUC Dubrovnik is the natural place for launching the transdisciplinary academy, in the Holotopia manuscript.

WAAS as Patron Institution

Here is how the World Academy of Art and Science introduced itself on its website.

The World Academy of Art & Science (WAAS) was founded in 1960 by eminent intellectuals including Robert Oppenheimer, Father of Manhattan Project; Bertrand Russell; Albert Einstein (posthumously); Joseph Needham, co-Founder of UNESCO; Lord Boyd Orr, first Director General of FAO; Brock Chisholm, first Director General of WHO and many others. The Academy serves as a forum for reflective scientists, artists, and scholars dedicated to addressing the pressing challenges confronting humanity today independent of political boundaries or limits, whether spiritual or physical….Our motto: Leadership in thought that leads to action.

Here is how I introduced the World Academy of the Systems Sciences and our collaboration in the Holotoopia book manuscript.

The above photo was taken at the joint workshop that the WAAS leaders had with knowledge federation at the Save Center Belgrade in 2017. The speaker is Garry Jacobs, the WAAS CEO and (now also) president; the title on the screen behind him reads “paradigm shift in social sciences”.

Collaborology Course as Medium

The collaborology prototype has been conceived as medium for transforming education; and for transforming the societal-and-cultural paradigm through education. It was prepared to be offered through the IUC Dubrovnik in 2016.

But we realized that quite a bit of documentation, and preparation, had to be done before this timely initiative can be set in motion.

In 2017, I presented and discussed this prototype at the WAAS Future Education conference in Rome.

We’ll need an in-depth dialog to elucidate how the collaborology prototype can be a medium to the IUC Dubrovnik to extend its activities online; and how it may help the WAAS make its mission impactful.

Here is how I introduced the collaborology prototype in the Holotopia book manuscript.