The human race is hurtling towards disaster. It is absolutely essential to find a way to change course.

– Aurelio Peccei

The word course in this report’s title is a reference to Peccei’s call to action.

He issued it in the opening lines of a brief book titled One Hundred Pages for the Future.

The Club of Rome—of which Peccei was the founding president—was an attempt (the most comprehensive and mature so far; and iconic in the knowledge federation prototype) to answer the question:

Where—to what condition or future—are we rushing toward at such speed?

For a decade, one hundred selected international experts—The Club of Rome members—performed a series of studies. Peccei’s call to action summed up their results.

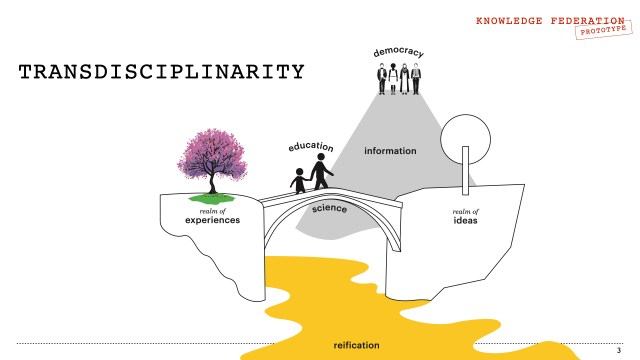

Transdisciplinary science constitutes a new paradigm in the humanities and social sciences.

The rationale—as I explained in We MUST Learn to Think in a New Way—is that the paradigm we associate with the word “science”, as it emerged from the Scientific and Industrial Revolution, worked well only for the natural sciences; and that this misbalance in our pursuit of knowledge resulted in profuse proliferation of weaponry and technology; and that the evolution of society-and-culture stagnated and fell behind.

In the opening of his 1969 MIT report and call to action, to institute a “transdisciplinary university”, Erich Jantsch quoted Norbert Wiener:

There is only one quality more important than “know-how”….This is “know-what” by which we determine not only how to accomplish our purposes, but what our purposes are to be.

This blog is part of—and for the moment the voice of—the holotopia initiative; where we undertake to reverse our society-and-culture’s self-destructive trends by restoring its provision of “know-what” to function to begin with.

Or—to use our standard metaphor—by replacing modernity‘s ‘candle headlights’ with the real thing.

We call our era “The Information Age”; am I justified in depicting our information as a pair of candles?

Before I proceed to show you some of the wonderful feats we’ll be able to achieve, some of the enchanting places we’ll be able to travel to once the right source of illumination is in place—let me take a moment and revisit this crucial question. An answer has been elaborated in the two most recent blog posts; so I’ll now offer you a very blunt summary—and leave its elaboration to our dialog.

Imagine that you and I are part of a large software company; and that we’ve found out that the software we (our company) are selling to people has some horrid and dangerous design errors; that its very working principle is in error.

Would we insist on making the requisite updates? Or would we remain silent?

That‘s the situation we—as academy—are in. That’s what I attempted to portray in We MUST Learn to Think in a New Way, by discussing those fundamental anomalies: Professional ethos, and good sense, demand that we give to people—especially to the young people—a different way to think; that we replace those hideous candles.

And there is an entirely different argument—which is (just as this one was) alone sufficient to reach the ‘candle headlights’ conclusions.

I chose not to speak about it in the two most recent blogs; but I did say quite a bit in my older blog posts. So let me here again jump to a conclusion:

Electrical technology has just been developed, and deployed globally; a paradigm shift in illumination is about to take place.

Doug Engelbart envisioned and created the technology you and I are using to communicate (through this blog) to enable the paradigm shift in ‘illumination’ we are here talking about. But ironically—no matter how hard he had tried—he was unable to communicate his vision to the Silicon Valley academic and entrepreneurs.

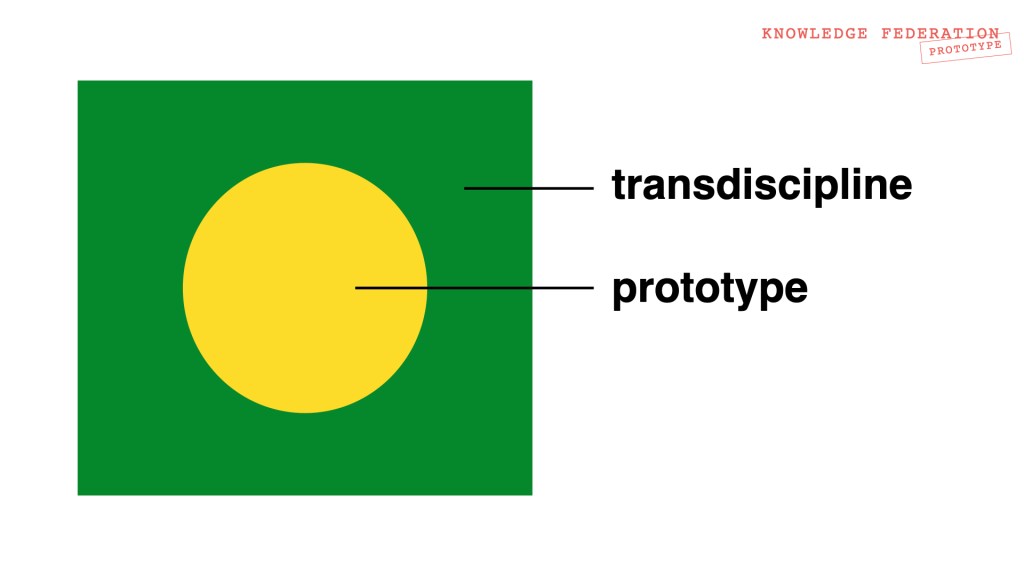

As I explained in this blog’s About article, to expedite the change of ‘headlights’, we created a complete prototype of a socio-technical lightbulb (transdisciplinary science). And made it available for inspection, eventual updates, and worldwide deployment. It is to set in motion that process that these three blog posts, and this blog as a whole, are all about.

In Knowledge Federation as Ecosophy I outlined its working principle; but since you’ll need the gist of it to comprehend what I’m about to show you, I’ll sum it up in two slides.

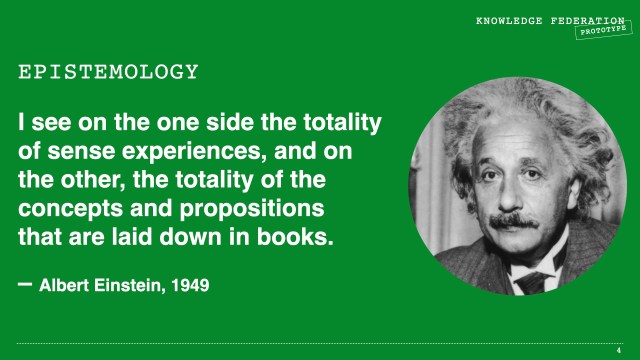

I let Einstein’s “epistemological credo” epitomize the fact that (the working principle of) transdisciplinary science follows directly from the fundamental insights reached in 20th century science.

“The system of concepts is a creation of man, together with the rules of syntax, which constitute the structure of the conceptual system”, Einstein explained further.

Transdisciplinary science empowers us to create concepts in the realm of ideas; and by doing that begin to theorize any chosen thing or theme.

And to then update its comprehension, or reconfigure its structure, by recourse to whatever may be relevant to it in the realm of experiences (which empowers us to draw insights from all records of and kinds of human experience; not only from scientific experiments); and by relating it with what’s known about other related ideas in the realm of ideas, by connecting the dots (which empowers us to reverse the comprehension and handling of life’s core themes by creating creditable theories).

What the Knowledge Federation as Ecosophy theme stands for—and that was the intended function of the corresponding event at the University of Zagreb—is the inspection and deployment or institution of transdisciplinary science. Based on what I’ve just said. Once again (I really don’t want you to miss this all-important central point):

The purpose of it all is to configure and begin a process; by which the academy—and society-and-culture—become capable of self-reflecting and evolving.

(You may notice that the academy began with that very intent, and process; when Socrates conducted the dialogues; and Plato recorded them, and instituted the Academy.)

This process has by now been finely designed and choreographed; and it’s patiently waiting for its next opportunity to take off.

What you’ll see here is an entirely different process.

Which is not academic self-reflection but a revolution; happening in any and all places where we the people have become weary of being mere spectators.

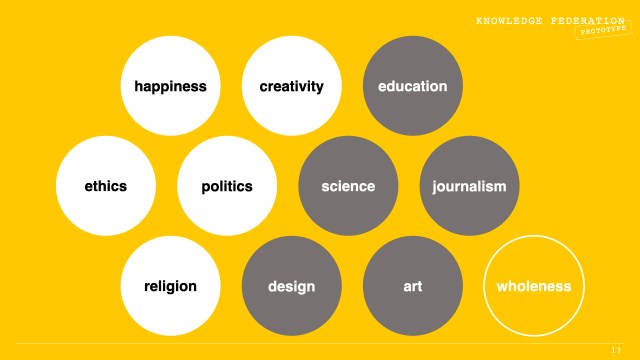

In our second event in Zagreb I offered the participants ten themes to choose from, and a claim; the event was conceived as an experiment.

My claim was that in each of those ten areas a revolution is ready to take place.

And will take place—as soon as we make the requisite updates in the way we think (as they’ve been detailed in the first event).

he first five themes—shown in white circles—constitute cultural revival examples. They are elaborated by federating insights—and showing why, for instance, ethics, or creativity, have to be comprehended and handled in entirely new ways.

The intended effect is to offer glimpses of a Scientific Revolution-like change—in the comprehension and handling of pivotal themes (the ones that determine modernity‘s evolutionary course).

The second five themes—shown in gray circles—constitute systemic innovation examples. They are elaborated by showing concrete, real-life prototypes of systemic redesigns in education, science, journalism, design and art.

The intended effect is to offer glimpses of an Industrial Revolution-like change—in the design and structure of pivotal institutions or systems.

Cultural Revival Examples

I’ll introduce the cultural revival themes by talking briefly about a recurring theme that is not one of them: How to put an end to war?

It was because of the risk of Nuclear annihilation that Russell and Einstein urged us to learn to think in a new way. And Peccei dictated these words to his secretary from his dying bed:

[A] premise of future-oriented thinking is quite evidently the absence of a nuclear holocaust….The primary mutation needed in our traditional outlook and values [is] freeing ourselves and our societies from the ‘complex of violence’ we inherited from our ancestors.

Why am I not including “war” as one of the themes? Because “war”—just as “climate change” and “poverty”—cannot be solved as “problems”.

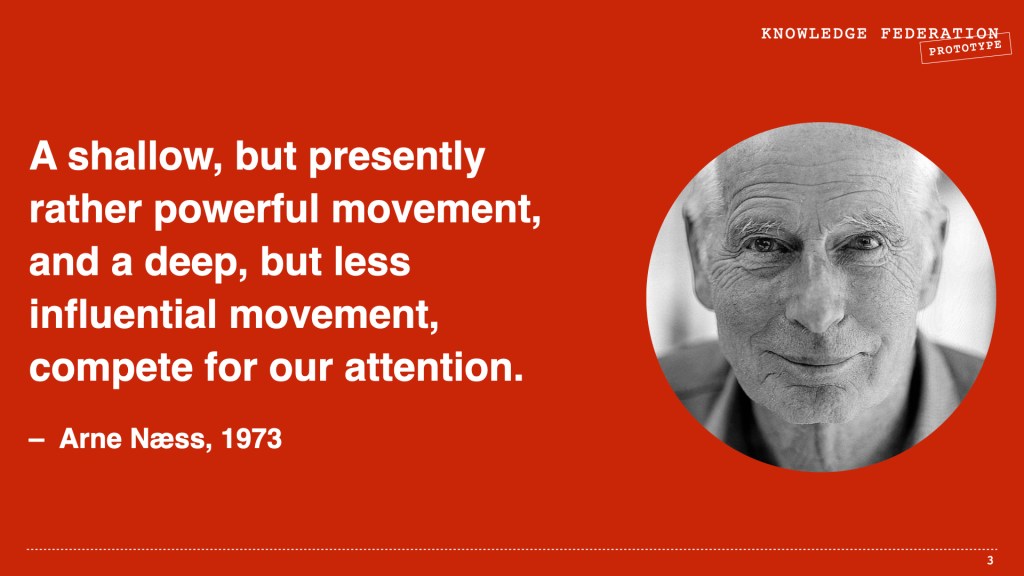

We’ll follow in Arne’s footsteps—and accelerate the deep work.

This vignette from the Holotopia manuscript will help you to see how putting an end to war hinges crucially on our ability to make substantial progress in the areas we will be discussing.

It’s hard to even imagine a theme more pivotal than “happiness”—considering that (in our present societal-and-cultural order of things) it’s regarded as the important “pursuit”.

I’ll be using convenience as keyword to point to a bias in our conception of happiness (which stems from the narrow frame way of thinking we’ve endeavored to unlearn):

Where we see happiness as a consequence and pleasurable things as its causes—and “pursue happiness” by seeking to acquire them.

The two examples I’m about to discuss will highlight that we’ll live considerably better—when we deepen our comprehension of happiness and update our pursuits. The first, called convenience paradox, was conceived three decades ago as a proof-of-concept result of transdisciplinary science (which was then represented by the buddying polyscopic methodology, conceived as a prototype of a generalized “scientific method”). The key point here is that a conscious or informed approach to information will naturally lead to a conscious or informed approach to happiness—which will have completely different results from the now common uninformed or mis-informed approach (think of all the advertising).

What constitutes an informed approach to information?

That’s what a methodology is meant to explicate.

The perspective criterion of polyscopic methodology states that information needs to illuminate what is obscure or hidden—so that we may see the chosen theme in correct shape and proportions.

The convenience paradox ideogram is a clear reference to the perspective criterion; which is here used to highlight that information needs to correct our perspective of happiness by illuminating the long-term consequences of our choices.

To really comprehend what goes on here—you’ll need to see it in the cultural revival context.

And trust me that there is a vast collection of (what’s in the knowledge federation prototype called) culture-transformative memes or simply memes; emanating from the world traditions, therapy schools, scientific studies…; ready to thoroughly transform our lives and culture. Typically, they’ll be opportunities to cultivate innate human abilities (and become creative, loving, effortless and so on). The first part, or half, of the Holotopia manuscript is all about that; there’s a multitude and a broad variety of examples; which constitute a revolution in culture ready to take place. But communication is the problem.

Conditioned to think in terms of (immediate) cause and consequence, and to confuse between happiness and convenience—we tend to ignore those memes.

In the Holotopia manuscript I introduced the convenience paradox result by explaining its ideogram.

The convenience paradox result was presented it as the second, application article (accompanying a preliminary outline of polyscopic methodology as theoretical article) at the Einstein Meets Magritte transdisciplinary conference; both articles were later published in the Yellow Book of the proceedings, whose title was Worldviews and the Problem of Synthesis. The intended contribution to this title theme was to show that when we acknowledge that the substance of information is human experience (and not “objective reality”)—we become empowered to synthesize precious heritage and insights across cultural and academic traditions.

And use it to illuminate the way to cultural revival.

This second and most recent example redirects our pursuits all the way—from “happiness” to wholeness!

Where the pursuit of wholeness—and this is the main point of the holotopia vision—calls for both inner (or personal and cultural) and outer (or systemic and institutional) transformations.

That creativity is pivotal is a truism; the comprehensive and complex crisis we are in may just as well be seen, simply—as the crisis of creativity.

Could creativity too be grossly mishandled owing to the narrow frame?

The second chapter of the Holotopia manuscript, titled “Liberation of Mind”, offers a carefully documented positive answer to this question.

It begins by a short anecdote involving Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen; to suggest that a certain now commonly ignored kind of creativity (which you might call real creativity, but in the book it’s called direct creativity instead) is everywhere in experience.

The “Liberation of Mind” chapter unfolds by showing that direct creativity—which, as you have just seen, both Einstein and Tesla averted us about—necessitates an entirely different creative process, and ecology of mind, compared to the now widely favored indirect creativity.

The point of Professor Raković’s research is to demonstrate that while direct creativity makes no sense within the classical view—it can be explain within the paradigm of quantum physics.

The first prototype in science I will discuss further below is the outcome of our collaboration to federate his result.

The Tesla and the nature of creativity prototype we crafted together constitutes a generic way to empower culture-transformative memes.

The creativity theme would be impermissibly incomplete without at least mentioning Abraham Maslow.

Thomas Kuhn published The Structure of Scientific Revolutions in 1962; Maslow published The Psychology of Science four years later, and partly as a response—to explain what prevents scientific revolution from happening; which gave him an opportunity to summarize the results of a couple of decades of research on the psychology of motivation, which he pioneered. Here is what he wrote in the chapter called “Safety Science and Growth Science: Science as a Defense”:

Science, then, can be a defense. It can be primarily a safety philosophy, a security system, a complicated way of avoiding anxiety and upsetting problems. In the extreme instance it can be a way of avoiding life, a kind of self-cloistering. It can become—in the hands of some people, at least—a social institution with primarily defensive, conserving functions, ordering and stabilizing rather than discovering and renewing.

The greatest danger of such an extreme institutional position is that the enterprise may finally become functionally autonomous, like a kind of bureaucracy, forgetting its original purposes and goals and becoming a kind of Chinese Wall against innovation, creativeness, revolution, even against new truth itself if it is too upsetting. The bureaucrats may actually become covert enemies to the geniuses, as critics so often have been to poets, as ecclesiastics so often have been to the mystics and seers upon whom their churches were founded…

Maslow’s main general point (encoded as “Maslow’s pyramid” or “hierarchy of needs, his best-known idea) is key to our liberation from the ‘complex of violence’ as Peccei called it, and from pervasive “free competition” as its milder form:

As long as don’t feel sufficiently (psychologically) secure that our “lower” needs will be met—we will not dare attend to our “higher” needs (such as “self-actualization” or true creativity).

Maslow’s main point regarding science (encoded as “Maslow’s hammer”, his second most famous idea) is that as long as our academic culture is as it is (think of the infamous “publish or perish”)—we’ll hold on to the ‘hammer’ (routine publication in “safe” i.e. established fields, using age-old procedures and tools).

And shun the possibility of more creative and more useful pursuits.

Ethics is the pivotal issue (if there is one).

And yet academy—and modernity—failed to give us a creditable clue.

All that one could say about this theme “objectively”—is that ethics is inherently subjective; and that a broad variety of theories have been proposed—and that no agreement has been reached.

There are, however, situations where ethical choices have to be evaluated.

Consider, for instance, this extreme case: If you bought a gun, and walked to your neighbor and shoot him—you’d have committed a “first-degree murder”. If, however, someone died in a distant part of the world, whose existence you ignore—then “obviously” you are “innocent”. These valuations are made, you’ll notice, based on whether someone “really is” innocent or guilty.

All this is thoroughly transformed when ethics is considered in the emerging paradigm.

And (instead of being reified) seen—just as information at large, of which it is a constituting element—as a human-made thing for human purposes. The question then becomes:

What does ethics have to be like—to serve us in its pivotal role?

And as soon as we begin to ponder this question—we find out that all but a negligible amount of suffering is caused, and has been throughout history, (not by “first-degree murderers”, but) by professionals sitting in armchairs and making “rational” business and political decisions. Here is how I pointed to this compendium of issues in the Holotopia book manuscript.

In what follows I’ll offer you two ways in which ethics as theme has been elaborated in the knowledge federation prototype.

Holotopia principle—a wholesale reversal of what’s become the norm—will follow as their synthesis.

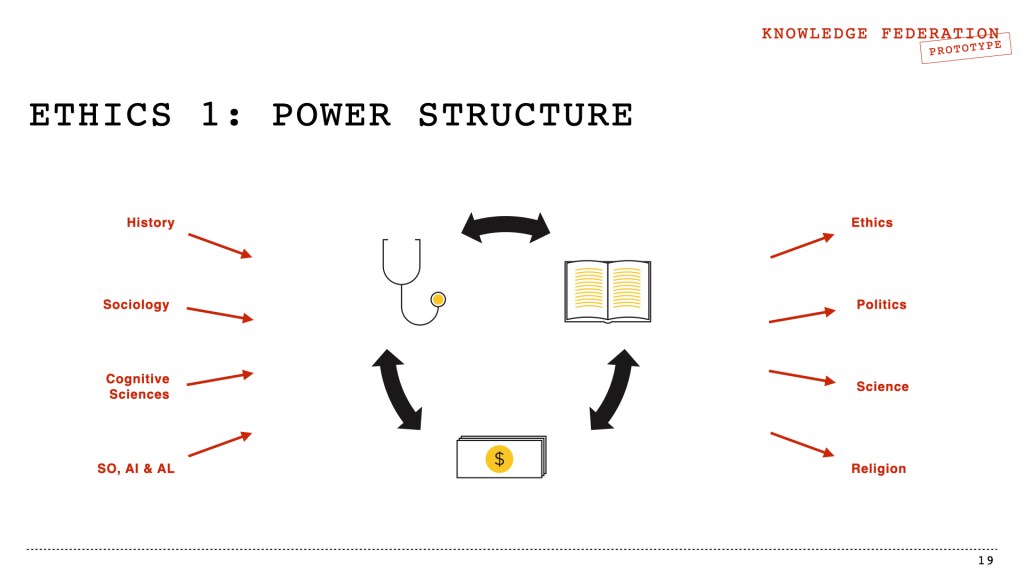

I offer you the power structure theory as the key to the impending societal-and-cultural paradigm shift (if there is one).

And also as the deepest and most far-reaching proof-of-concept result of transdisciplinary science so far (excluding the holotopia vision which is the synthesis of them all). Regrettably, this means that you would need a deeper understanding of the polyscopic methodology, and quite a few more data points, to really comprehend it. So this will be a rough sketch.

You may see it (as the above image might suggest, which has the power structure ideogram in its middle) as an outcome of combining the most basic insights reached in the humanities—to illuminate the main thing we still ignore about ourselves and our society; how renegade power really operates. (No, this is not a conspiracy theory; but it has similar effects!)

Let’s cut this to the bone; and only illustrate it by this excerpt from Wikipedia:

In sociology, the iron cage is a concept introduced by Max Weber to describe the increased rationalization inherent in social life, particularly in Western capitalist societies. The “iron cage” thus traps individuals in systems based purely on teleological efficiency, rational calculation and control.

Weber wrote The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism more than a century ago, at the point of inception of scientific study of society; and it is still required reading to social science students worldwide. And yet his most famous insight has not yet been digested and assimilated in our popular worldview, ethics and politics.

Which is that the relationship between our (increasingly “transactional” or “instrumental”) thinking and our (increasingly oppressive and dysfunctional) institutions or system is the major source of economic and political power; which doesn’t serve anyone’s “real interests” (even though we believe it does)—only the “interests” of the power structure itself.

That’s what the power structure ideogram points to: The stethoscope in it stands for (the lack of) wholeness, and points to the condition the power structure keeps us in—which is reflected both in the deformations of our systems (in which we live and work) and in our own stressed and empty lives. The book points to information—which includes also our ethical norms, and the way we think.

The dark arrows in this ideogram suggest that the relationship between our information and our (lack of) wholeness is where the bulk of renegade power resides.

Which has to be illuminated by (suitably designed) information; without which we tend to focus on mere symbols of power (such as money; or the person of the US president); which constitute a mere shadow play on the walls of the cave (on which our vision tends to be fixed).

The main point of the power structure theory is to explain the evolution of the power structure (and this is where Weber’s reference to “Western capitalist societies” comes in; and also the most cryptic reference to “SO, AI & AL” on the power structure ideogram—which are the technical fields where the emergent properties of Darwin-style evolution have been studied and comprehended).

So here is what all this comes down to practically:

“Free competition” is the sufficient cause for the power structure to emerge.

Which (in this informed or holotopian view of ethics) translates into the following ethical message:

The behavior that is now commonly considered “normal” or “ethical” (where we ask What’s in it for me? and act accordingly) is the sufficient condition for our civilization’s demise.

Nothing more than sitting in armchairs and making “rational” business and political decisions is required—for someone (and arguably for most of us or even for all of us) to be culpable (when emergence—and not only causality—is taken into account) of geocide (the cruelest massive crime in human history).

I presented the power structure theory at the InfoVision2000 conference in Coventry, Great Britain; where it was invited for publication in the Information Design Journal; which resulted in two articles: “Information for Conscious Choice” (where the power structure theory was introduced) explained why we must not rely on “free competition” (or in other words, why “conscious” or informed choice has to take its place); “Designing Information Design” was another methodological article, showing how to design the requisite information.

The second way to see ethics in a new way is the holotopia vision; which complements the power structure theory—by showing what we need to do to create a whole inner and outer condition.

The holotopia vision is not a future vision in an ordinary sense—but what one might see when proper light’s been turned on. It’s rendered in terms of five insights (in the context of which other pivotal themes are comprehended differently) and two principles (ethical rules or rules of thumb, which thoroughly redirect how we think and act). Here too I’ll condense a large collection of game-changing insight to a single main point.

The ethos that is not supported in the competitive world—to (transcend “personal interests” and) collaborate to make things whole (all things, including both ourselves and our systems)—is a necessary condition for a new paradigm (or “a better world”) to emerge.

This far-reaching conclusion follows:

When we compete (to further what the power structure made us see as “our own interests”), we end up co-creating the power structure; when we learn to collaborate (and make things whole), we’ll be able to co-create the holotopia.

Did you notice the irony? We’ve come back to the ethics shared by the Great World Religions! Only the afterlife is no longer needed.

The ethics we live by will make the difference between heaven and hell—here on Earth!

The holotopian politics (where we’ve freed ourselves and our societies from the ‘complex of violence’ we inherited from our ancestors, exactly as Peccei demanded) follows directly from the holotopian ethics you’ve just seen.

Can you even imagine a world where political action is conceived as collaboration (to unravel the power structure, by co-creating systems), and not as strife and competition?

To see why holotopia is not a utopia, you may have to get accustomed to looking at the systems (in which we live and work) and seeing how much they’ve been mutated or mutilated by the power structure. See if this short excerpt from the Holotopia manuscript may help you make this adjustment.

Does God exist?

Before we step through the mirror, while we still look at the world through the narrow frame—the issue and destiny of religion will tend to be decided by considering that question.

On the back side of the mirror—we’ll recognize the question itself as part of the narrow frame; and ask:

What may religion have to be like—if we and our society are to be whole?

And then, also:

What do we still need to comprehend, and integrate into our society-and-culture—from the legacy of the world religions?

I offer the following two ideas to our dialog about religion.

Is there a “law of nature” or phenomenology that underlies religion?

Buddhadasa—Thailand’s holy man and Buddhism reformer—left us a far-reaching positive answer to this question (“far-reaching” because the phenomenology he discovered offers us a way to transform both the consumer society and religion).

Here is how I introduced Buddhadasa in the Holotopia manuscript.

One of the ways to read the Holotopia manuscript is to see it as part of a carefully crafted action plan to federate Buddhadasa’s insight.

Which constitutes another general template for federating culture-transformative memes.

Chapters One to Five offer a sketch of inner or personal wholeness; Chapters Six to Ten draft outer or societal-and-cultural wholeness.

Chapters Five and Six place the Buddhadasa meme onto this roadmap to wholeness.

And demonstrate that it completes the map; that neither we nor our society can be whole without it.

Chapter Five presents the Buddhadasa meme as an integral part of our inner wholeness. Here is how it begins.

Chapter Six shows that what Buddhadasa discov as the shared core of the Great World Religions is indeed an integral part of our other or social-and-cultural wholeness. Here is how this chapter begins.

What is religion?

Or more to the point—How do we need to see and define religion?

You may here recall the transdisciplinarity ideogram, and how transdisciplinary science (as modeled within the knowledge federation prototype) operates: That we first create a concept (in the realm of ideas), and then federate what we need to know about it.

Why not handle religion in this way?

This excerpt from the Holotopia manuscript will illustrate what that might lead to.

Systemic Innovation Examples

Every paradigm brings to the fore entirely new ways to look at the world; from which new issues and different priorities naturally follow. Once considered central—”angels”, and “original sin”, are no longer points of concern at our universities.

Can you imagine a similarly dramatic shift of academic priorities today?

This of course won’t happen overnight; neither do I expect to convince you by these cryptic comments. So let me here only direct your attention toward something that—I have become increasingly convinced, during these thirty years of “trying to change the system fro within” (to echo Leonard Cohen’s words; but he sings them so much more convincingly)—is the pivotal point around which the paradigm will change. And as these things go—this pivotal point doesn’t yet even have a name in our shared language, and awareness. So as I said—all I can give you at this point is a cryptic hint. Here it is: It took the societal-and-cultural evolution (or the power structure) all this time to—finally—turn us into obseervers. To condition us to accept the societal-and-cultural world we live in as the “reality”, and confine our action to role play. There can be no doubt that technology—and information media in particular—helped; and I doubt if any of us truly comprehend this. I am certainly still struggling with it.

This is what I’ve really been trying to point to by talking about that mirror.

We have to learn to (not only see, but also) treat our society-and-culture as something we’ve created—and may as well create differently. What is so difficult about it is that we so deeply embody this conditioning; to confine our action to role play.

This is what our dialog will really be about; and what (I’ve become increasingly convinced) Socrates and Plato too struggled with.

As I mentioned—the knowledge federation transdiscipline is conceived as society-and-culture’s evolutionary organ; and systemic innovation is that evolution!

Systemic innovation is not yet represented at our universities.

That’s what Erich Jantsch attempted to change—more than a half-century ago, at the MIT; and what Doug Engelbart was struggling with throughout his long career. But Doug and Erich are still unknown heroes. Galilei is still in house arrest.

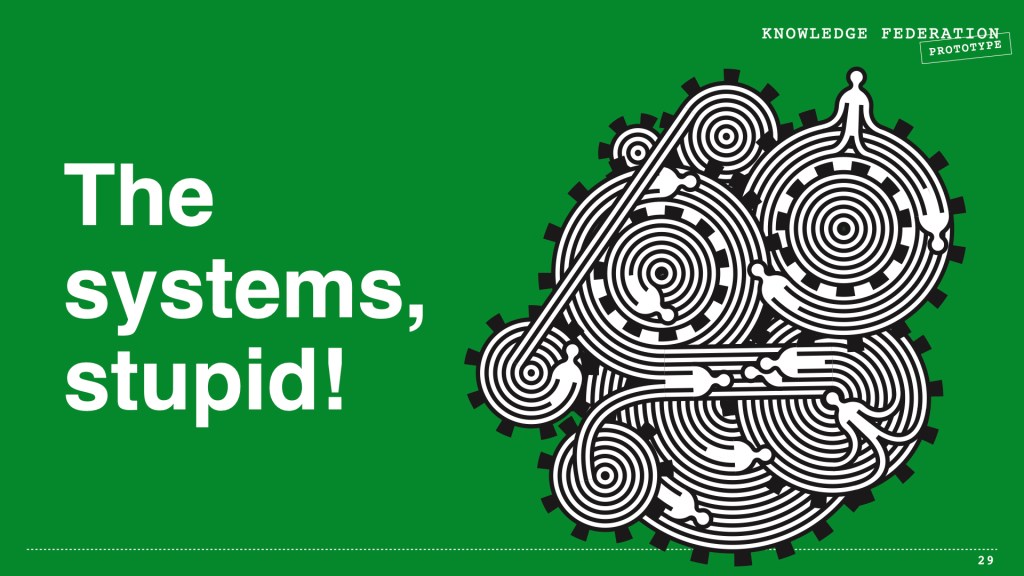

But let me calm down; let’s take this a step at a time. What I’m calling systemic innovation is also one of holotopia‘s five insights. But this all too technical or clinical name doesn’t do justice to that breathtaking Oh my God! experience that results when we’ve readjusted our vision; and instead of looking at “problems”—we zoom in on the systems that underlie them.

The first step is to see the systems (in which we live and work) as gigantic (socio-technical) ‘machines’.

The second step is to—slowly but surely—readjust the way we act. See if this excerpt from the Holotopia manuscript might help you get started.

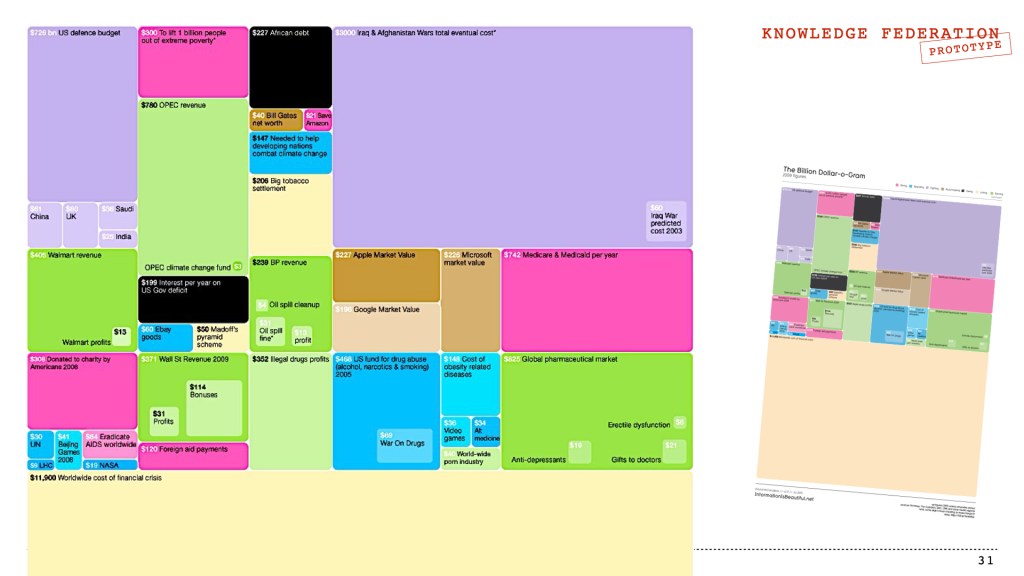

McCandless created the Billion-Dollar-o-Gram to help us see “problems” in a correct perspective.

The legacy of Erich Jantsch and Doug Engelbart has to be on our map—when we are making a case for transdisciplinarity as a way or arguably the way to change course.

This very brief excerpt from the Holotopia manuscript will do for the moment.

Systemic innovation is conceived as co-creation of prototypes.

Each prototype is defined in terms of a collection of design patterns; which are design challenge-solution pairs. Each design pattern constitutes a standalone “invention” or “result”.

While together—they show how an institution or system can be made whole.

Education being so obviously pivotal (it reproduces the world with every new generation)—innovating education is perhaps the most obvious way to change course.

The collaborology prototype has been developed to showcase and prime this approach.

Like most other system prototypes in the knowledge federation portfolio—the collaborology prototype is both a result of systemic innovation (of education) and a system enabling systemic innovation (in all walks of life). Did you get that?

How to change education so that creativity—and direct creativity in particular—may be supported? Let’s talk about this design pattern first. Here is how I introduced it in the Holotopia manuscript.

A related and equally acute design challenge is to make the society, or the power structure, pliable and transformable. Consider (to illustrate this need by a concrete instance, one among so many) the U.S. military-industrial complex following the end of the World War II; or consider any other profession that may become less or no longer needed.

Collaborology offers a practical means of re-education; at any point in one’s life or career.

The same solution—the one you’ve just seen—works.

Furthermore—collaborology offers education in technology-enabled systemic innovation; and more generally in those areas where we’ll need people—as the paradigm shift unfolds.

As an innovation of the academic system, collaborology offers a sustainable business model for creating any new academic field, or profession; for creating (a state-of-the-art) something out of nothing.

What makes this work is that exactly that—the creation of a new body of knowledge—is the creative challenge extended to the students; which they share with the faculty.

And that “the faculty” is not an academic department—but a network; comprising creative leaders across the globe.

Collaborology implements the game-changing game.

Collaborology is the game-changing game.

If you’ve seen Information Age Coming of Age, you’ll recall that the game-changing game is a practical way to change systems; and a practical way to empower our next generation to create the systems in which they’ll live and work—and in that way craft real “solutions” to global “problems”. The way this works concretely, in the collaborology prototype, is that the “students” (who may be self-selected graduate students from international universities; or entrepreneurs looking for their next project; or creative people in search of a career) form teams and (with the aid or direct participation of collaborology’s similarly international and diverse “faculty”) co-create system prototypes.

The collaborology prototype has been in evolution—initially as the University of Oslo transdisciplinary Information Design Course—since the year 2000. The key technical innovation (initially called “polyscopic topic map”, and later domain map object) was presented at the IEEE yearly conference on Advanced Learning Technologies in Taipei, Taiwan, in 2005; where it was invited for special issue journal publication.

We were prepared to offer the collaborology course internationally through the Inter University Center Dubrovnik in 2016; and decided to wait.

In 2017 I presented and discussed the collaborology prototype at the World Academy of Art and Science 2nd International Conference on Future Education in Rome.

To me it’s the system of science where that Oh my God! feeling (that something is stupefyingly out of sync) is at its strongest. Not—certainly not—because this system is the worst of them all.

But because this system is where some of the smartest people on our planet live and work!

And if they cannot do better… Well of course—this problem has been noticed; and (some) scientists have tried to produce a solution. When in 2010 the Knowledge Federation R & D community began to self-organize as a transdiscipline (and become the academy‘s and the society’s evolutionary organ), we wrote this article to motivate this initiative.

I will illustrate the prototypes we created to showcase systemic innovation of scientific production and communication (which, as we pointed out in the article, Bourdieu identified as the critical path to improvement) by two examples.

When a scientific result has been published in an academic journal, it is common to consider is as “known” and move on to the next task.

Can we make that assumption?

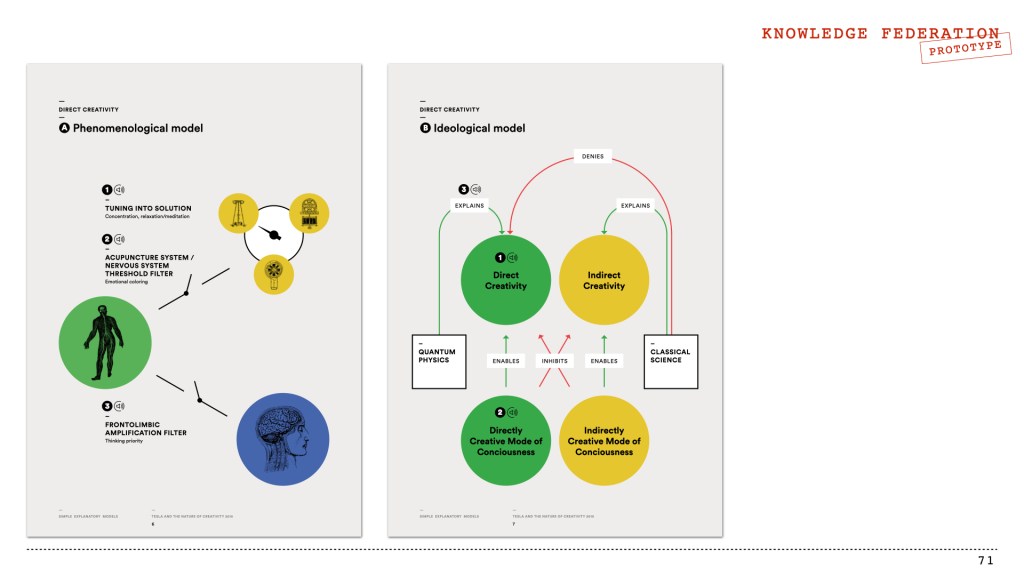

Tesla and the nature of creativity prototype was conceived to showcase an alternative; to show how the communication of an academic result can be re-designed, and made considerably more effective.

It suited our purpose that the specific result at hand was written in an inaccessible professional language (of quantum physics); and that it had an uncommonly large potential general impact (to revolutionize creativity).

Tesla and the nature of creativity prototype.

The Tesla and the nature of creativity prototype has three phases.

The function of the first is to extract the main ideas from the research article, and make them comprehensible to nonspecialists.

To that end, Fredrik turned Dejan Raković’s research article into a multimedia object, featuring three ideographic maps; of which I’ll show you two, for illustration.

The “phenomenological model” explains how (Tesla-style or) direct creativity functions.

It offers what one may need to know in order to to use or emulate direct creativity—or to teach it to students.

The “ideological model” extracts the main ideas from the article—and makes them available for online federation.

Both graphic maps are equipped with icons. By clicking a loudspeaker icon, you’ll hear an audio recording of my interview of the author—where the corresponding part of the model is explained in an accessible way. By clicking a number icon, you’ll see the section of the research article where the corresponding part of the model is elaborated in technical language.

The second phase of the three-phase federation was a face-to-face dialog.

We benefited from the presence of international researchers of the Tesla phenomenon and Tesla biographers, who gathered in Sava Center Belgrade for conference, and organized a one-day workshop where the presented creativity models were scrutinized. Is this really how Tesla thought and worked?

This workshop also gave us a chance to make the models known to Serbian and international audiences (the workshop was streamed online, had virtually present international participants, and summarized on Serbian TV).

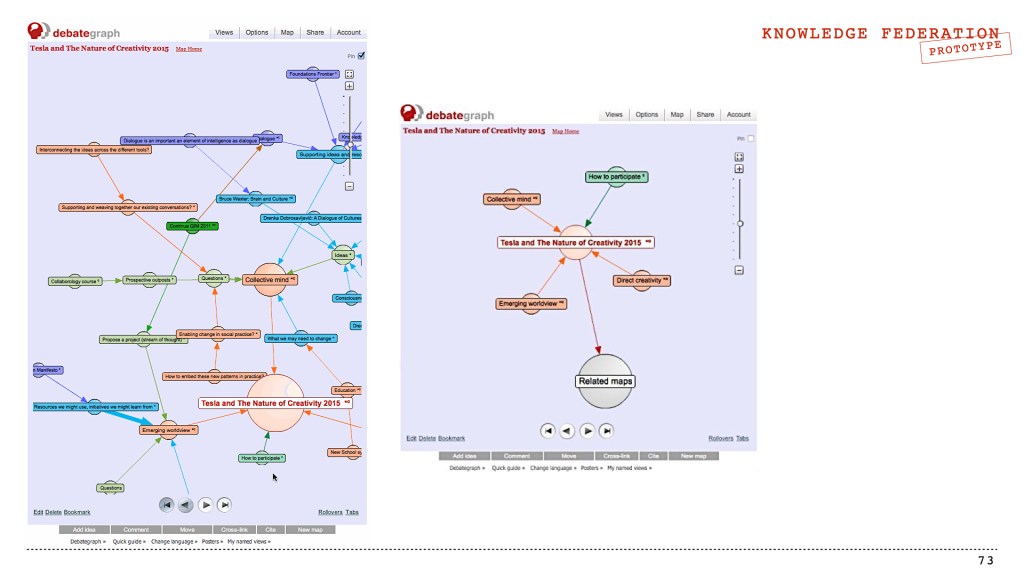

The third phase was an online federation of the article’s main ideas.

Here we used DebateGraph—a state-of-the-art online deliberation tool.

DebateGraph—and the “issue-based information systems” it is based on—was created for collective unraveling of any issues, and in particular those so-called “wicked” ones (whose solutions or even definitions evade us). We adapted DebateGraph to deliberation of academic results. Here is how this works: Each DebateGraph node has a type; which in our case may be “claim” (which the author made in the article that’s being federated). Then several other node types can be added—for instance an argument pro, or con, or a supporting reference and so on. Do you see where this is leading us?

It is possible to create a thoroughly novel social life of information—which is so much richer than the “peer reviews” we presently have.

(This entirely new process is, by the way, precisely what Doug Engelbart had in mind—when he undertook to create the interactive, network-interconnected digital media, which are now in common use. Doug used CoDIAK as acronym to name it; which stands for Concurrent Development, Integration and Application of Knowledge. The key point here is that the new media technology constitutes “a collective nervous system”, which enables people around the globe to think and create together, as cells in a single human mind do—instead of only publishing or broadcasting; which is the process that the old technology, the printing press, made possible.)

The lighthouse prototype (which showed how a key insight emanating from a research field may be synthesized and communicated to academic and general audiences) complemented the one I have just outlined (which showed how to federate a single result). The research community was the International Society for the Systems Sciences.

The key insight that the lighthouse undertook to federate—that we cannot and must not rely on “free competition” to steer (the evolution of) humanity’s systems—was reported by Norbert Wiener in his 1948 seminal book Cybernetics (as part of the motivation or arguably as the motivation for establishing cybernetics as an academic field). This insight is pivotal in two regards:

- It is key to modernity‘s change of course (from power structure-driven to information or knowledge-driven, as explained above)

- It is key to giving impact to the systems sciences (because it is only when we stop believing that “free competition” is all we need—that we’ll be ready to listen to what the systems scientists have been trying to tell us).

This serendipitous photo of our initial project team (to which Fredrik later added the light, and made the point) was taken at the 59th yearly conference of the International Society for the Systems Sciences in Berlin; whose titled was, coincidentally, Governing the Anthropocene. The Lighthouse prototype was completed for and at the subsequent ISSS conference at the University of Colorado at Boulder.

Here is how I described the lighthouse in the Holotopia book manuscript.

We crafted our journalism or public informing prototype at our 2011 workshop in Barcelona; which had the long title “Barcelona 2011 Innovation Ecosystem for Good Journalism”; which calls for a brief explanation.

Here too there is a methodological article—I reported about it Knowledge Federation – an Enabler of Systemic Innovation. Here is how the described method works.

A transdisciplinary community is created around a prototype—with the mandate to evolve it (by combining requisite types of expertise) and give it real life and impact.

Our workshop in Barcelona was designed to serve as a proof-of-concept application of this way of working.

I’ll highlight two of its design patterns.

The challenge of the first was to bring together requisite sources of expertise—and foster a functioning transdiscipline.

This combination of three photos and names is intended to be used ideographically—and illustrate how we handled this challenge.

Paddy Coulter had been both a premier journalist and the Dean of Oxford University’s Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. In the manner of giving the tradition of good journalism the reigns—we invited Paddy to chair the Barcelona event.

Mei Lin Fung has been the leader of the Program for the Future R & D community—which shaped itself around Doug Engelbart, to secure further evolution to his legacy and vision. It is easy to see how Engelbart’s best known idea (that information technology has to be used to drastically augment our “collective intellect”—our collective capability to comprehend and resolve our increasingly urgent and complex problems) has exactly in public informing its important application.

David Price has been a co-founder and leader in both DebateGraph (as arguably the leading collective intelligence project) and Global Sensemaking R & D community.

The second design pattern I’ll mention had the design of a remedial public informing as challenge.

I used design as a keyword to highlight that (instead of reproducing the traditional news format, instead of reifying the ‘candle’ as the ‘headlight’)—we asked and answered the question What may public informing have to be like—to empower us to find and follow a remedial course?

We visualized the prototype answer that resulted as two loops—one placed on top of the other.

The function of the lower loop was news aggregation; it was doing, roughly, what the conventional media do—but in a different way. We built our solution on the Barcelona WikiDiario citizen journalism project (whose founders were in our team)—where the citizens (democratically, and predominantly) were given the opportunity to create news content (and voice their concerns, and point to problems, directly); which was then curated by professional journalists.

The function of the upper loop was to identify and explain the systemic causes—and solutions—to reported and selected problems. This loop involved academic and other experts; and creative communication design—whereby systemic causes, and solutions, were made comprehensible and palpable to the public.

If you’ve followed me this far—you’ll have no difficulty seeing why we have to update democracy in exactly this way.

And how that will help us change course.

The paradigm strategy prototype (which we contributed to the 2017 Relating Systems Thinking and Design international symposium that was organized here in Oslo) was an instance of a series of prototypes called key point dialogs.

Here you may see Fredrik Eive Refsli—knowledge federation‘s chief designer—jubilating its creation.

The function of a key point dialog is to enable a community of people—which may be the global community—to reach a direction-changing insight.

Which in this concrete case was to shift focus to comprehensive or paradigm change—as a better alternative to wrestling with “problems”.

This prototype constituted also an academic system redesign.

The QR codes on the poster enabled the symposium participants to open its online interactive version; and contribute to the design of this key point dialog.

It is enough to bring to mind Boticelli’s iconic paintings—to realize that art has to give voice to transformative ideas; to give shape and color to also this cultural revival.

The Earth Sharing art prototype I am about to show you had also this design pattern:

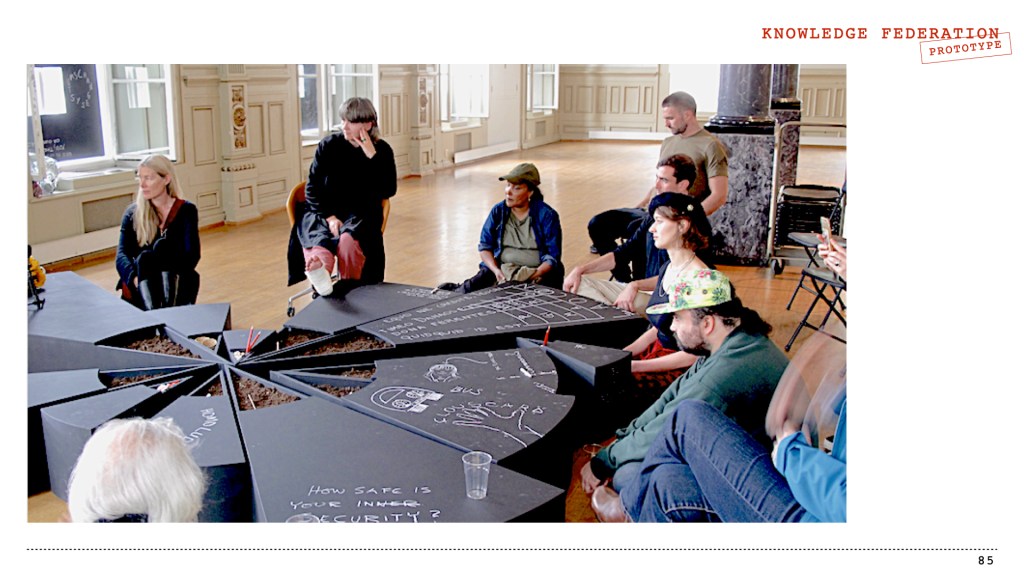

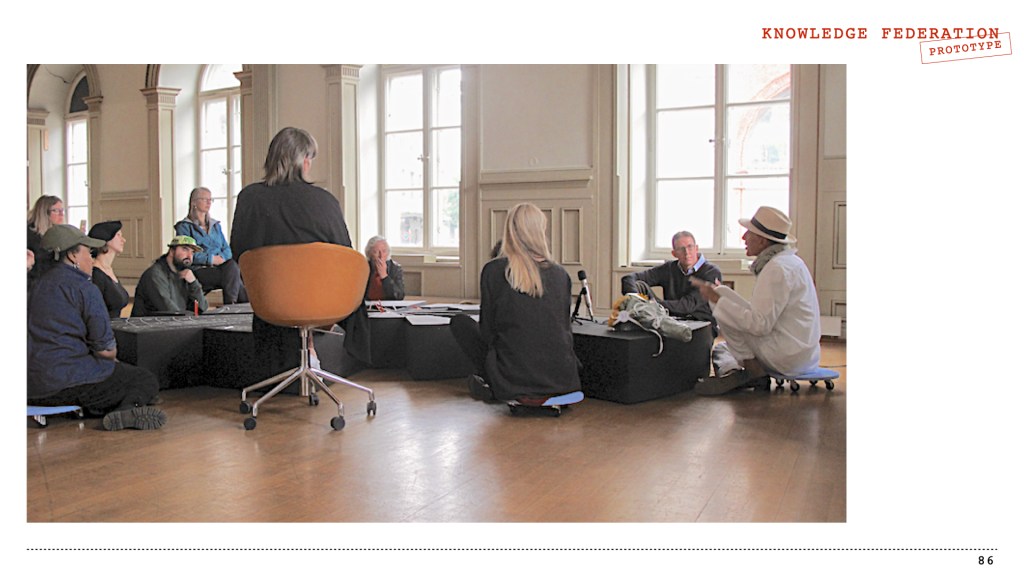

The artist created a transformative space; which included a process and means of interaction for changing course.

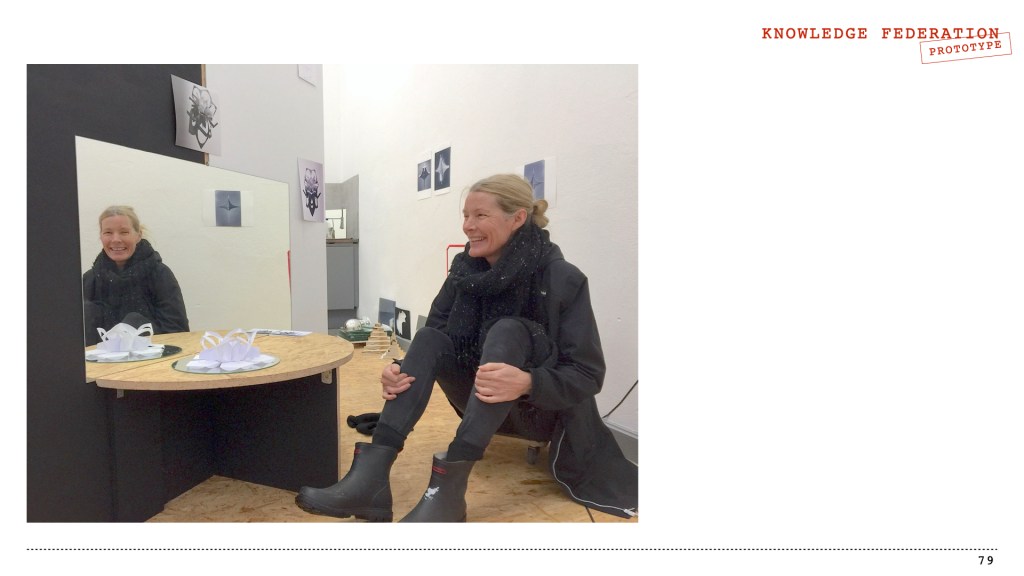

Here you may see the artist—Vibeke Jensen—in her Berlin studio; facing the mirror with a paper model for a holotopia sculpture in front of it.

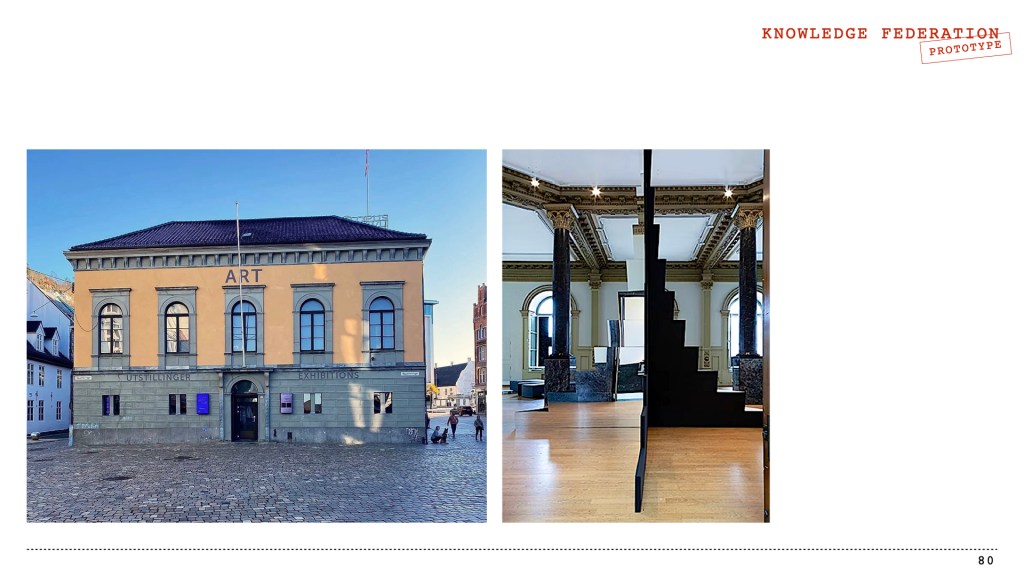

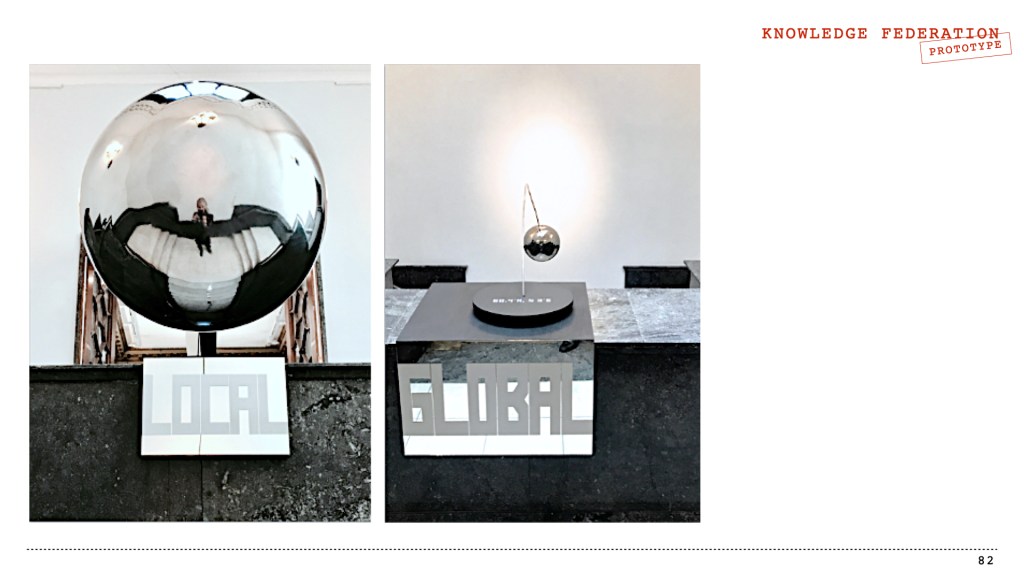

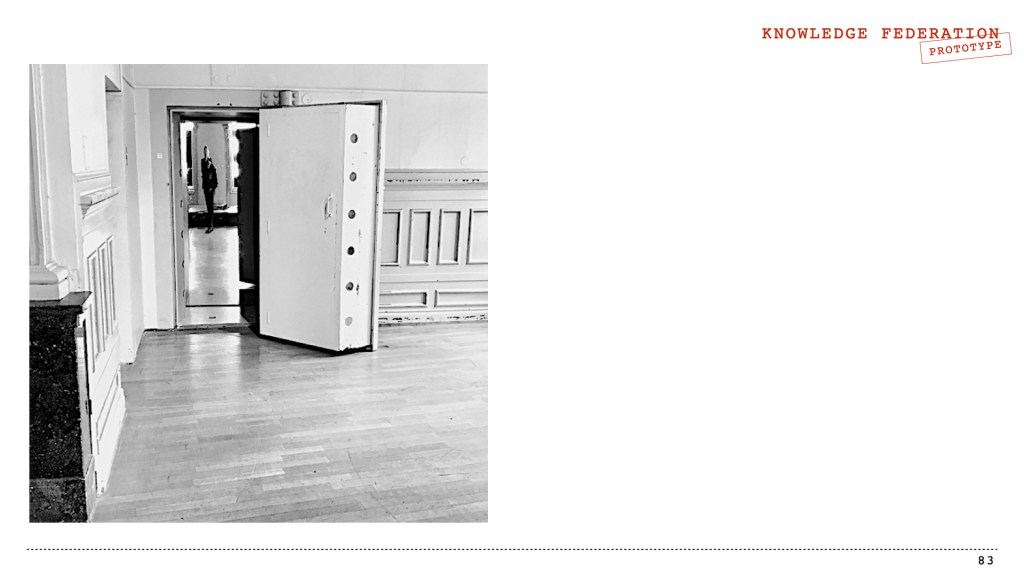

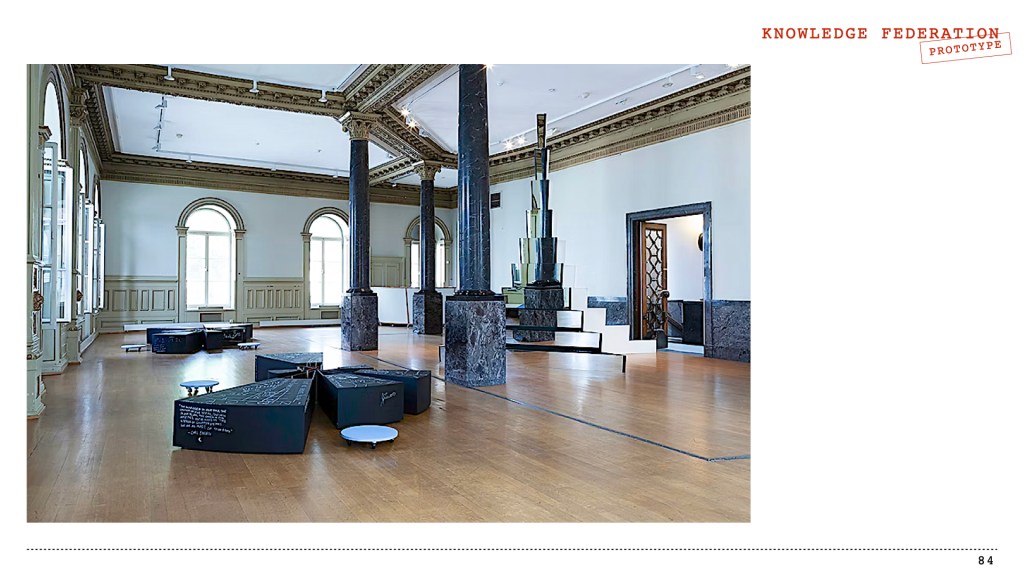

The Earth Sharing project was staged in the 3.14 art gallery in the old center of Bergen; in a building that used to be a bank. Above right is a sculpture of the metaphorical mountain (leading upward, toward higher insight); which had a mirror side (leading toward inward insights).

The core elements of “new thinking” we’ve been talking about—notably that it combines distinct levels of abstraction—lended themselves to artistic expression.

The main point of the installation was to foster a collective transformative space.

The bank vault was transformed into “safe space”; which was entered through a one-way mirror; whose interior was dark—but one could see “the world” outside; while listening to dialog excerpts that Vibeke and I recorded—which offered food for thought.

And with renewed energy and insight—join the collective co-creation.

Where suitable media were provided to record—and communicate further—its fruits.

Zagreb Event as an Experiment

Transdisciplinarity Is the Way to Change Course—our second dialog in Zagreb—was staged in the colorful premises of the Croatian Association for Philosophical Practice; which is de facto Croatia’s café philosophique.

It attracted a larger—and also more diverse audience than the first event.

We shared this flyer to announce it.

The setting and the audience seemed just perfect—and yet our communication once again completely failed.

There was not even an inkling of the transformative process we intended to set in motion.

So we said—OK, let’s try again; and reconfigured this blog; to serve as a runway for launching future dialogs.

Did I manage to make it clear that the function of holotopia dialogs is to transform communication and the world through communication (and not only to communicate)?

Do you see why we have to engage in this line of work—and feel inspired to join our next dialog?